A Successful Commercial Icebreaker Program: Le Commandant Charcot

An Icebreaker comparable to the planned Polar Security Cutter, designed and built in less than six years, for about one-third the price.

During the recent Congressional Subcommittee hearing (which I wrote about here) that took a look at the delays and cost overruns of the Polar Security Cutter (PSC) program, one of the witnesses was asked to provide an example of what a good private shipbuilding design and construction program looked like. The witness could not provide an example on the spot.

For such an example, allow me to walk you through the design and construction of Le Commandant Charcot.

In early 2016, Ponant, a French luxury cruise line known for its adventure cruises, approached the Finnish engineering and design firm Aker Arctic with an idea:

“We started with a crazy project to take people on the path of the French polar explorer Captain Jean-Baptiste Charcot, going where no other vessel is capable of going,” says Mathieu Petiteau, Ponant’s newbuilding and research and development director. “It was pushing the polar adventure to the limits to offer something that is comparable to going to the moon.”

Petiteau continued:

At the beginning, they [Aker Arctic] thought we were completely crazy. An icebreaker and a cruise vessel cannot be mixed together. An icebreaker is a heavy-duty vessel that makes a lot of noise and vibration, and it’s not comfortable at all. A passenger ship is the opposite. At the beginning they were a bit skeptical. But in the end, they said, “Let’s go crazy, folks!”

Before beginning design work, Ponant and Aker Arctic worked to determine the icebreaking requirements:

For four months, we collected a lot of data and performed environmental analyses to come up with some design criteria for the temperature, ice thickness and the size of obstacles.

To go to the North Pole between June and September, the vessel must withstand minus-25 degrees Celsius. We needed to be able to break 2.5 meters of thick, intact ice—not because we will always encounter this type of ice, but because we cannot get trapped if we want to safely come back to port on time to pick up new passengers and maintain the schedule.

Then, the vessel needed to be able pass through obstacles—ice ridges, where two ice plates are pushed together by the current or wind to create very thick ice.

Aker Arctic’s resulting design

is a modern PC 2 icebreaking hull design, which combines smooth icebreaking ahead in up to 2.5 m thick multi-year ice, and astern in severe ice conditions using a double acting ship principle (Aker Arctic DAS™) and a twin azimuthing propulsor arrangement. The vessel's performance is comparable to existing polar icebreakers but with lower ice resistance ensuring better fuel economy. This concept is the first commercial application of its kind for both efficient icebreaking and open water operation in high arctic conditions.

Construction Begins

In December of 2017, Charcot proceeded towards construction as Ponant signed a NOK 2.7 billion contract (about $323M USD at the time) with the Nowegian-based shipbuilder VARD1 for its design and construction. The team2 now included Ponant, Stirling Design International, Aker Arctic, and Vard.

Less than one year later, in November 2018, construction began at Vard’s Tulcea, Romania shipyard. Charcot’s keel was laid about one month later on December 14, 2018.

From Romania to Norway and France for Completion

On March 29, 2020, about fifteen months after the keel was laid, Charcot left Tulcea under tow en route to Vard’s Søviknes shipyard in Norway for outfitting, with a short trip to France in July for installation of the Azipods.

Ice Trials and other tests

Charcot completed sea trials and a test of her propulsion system in April 2021, and completed ice trials in June 2021:

Le Commandant Charcot headed first north to Svalbard, and then west towards Belgica Bank off the east coast of Greenland. Propulsion adjustments were made before the ice trials started. The voyage continued along international waters to areas northwest of Greenland in search of suitable ice fields.

Le Commandant Charcot is designed according to the Double Acting Ship (DAS™) principle which allows the vessel to operate both in ahead direction as well as stern first, depending on the prevailing ice conditions. Tests in ahead direction were conducted in two level ice thicknesses: 2.0 metres and 2.7 metres. Le Commandant Charcot was found to be able to maintain continuous motion even in the thicker ice. Stern-first tests were done in up to 1.7-metre-thick level ice. In addition, the vessel could penetrate a heavy ice ridge without any problems.

National Geographic has some footage of Charcot’s ice trials in this video promoting an episode of Megastructures:3 (aired June 2023)

Delivery

Vard delivered Charcot to Ponant on July 29, 2021, about five and a half years after design work began, three and a half years after Vard accepted the contract, and two a half years after the first steel was cut.

Dry run to the North Pole

Before Charcot’s maiden cruise, Ponant organized a dry run to the North Pole in order to train the ship’s crew and test all of the ship’s equipment, including the polar safety gear, as required to earn a PC2 notation.

On September 6, 2021, Charcot the first French-flagged vessel, first cruise ship, and the first LNG powered hybrid vessel reached the North Pole.

Aker Arctic had two representatives onboard during the dry run who commented on the ship’s seakeeping:

The vessel achieved its performance targets smoothly with hardly any noticeable vibrations from icebreaking4. The ship’s double-acting ability to break ice when sailing ahead or astern was tested in ice ridges to check the comfort level for passengers.

Comparing Charcot to the Polar Security Cutter

At this point, some of you might be thinking, “okay, you can build a cruise ship that breaks ice in less than six years from the start of design. The U.S. is building a heavy polar icebreaker. This is an apples and footballs comparison.”

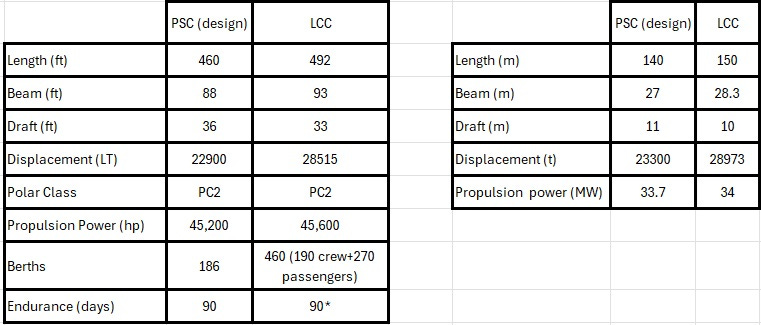

Let’s start by looking at the size and capability of Charcot against the planned size and capability in the Polar Security Cutter (PSC) design. The PSC numbers come from VT Halter’s design, as reported in their press releases. Numbers for Charcot are from public releases by Ponant. For ease of comparison with other vessels, I am presenting the data in both imperial and metric forms.

As you can see, the vessels are similar in size and capability although Charcot is slightly larger and more powerful. (Note that it is not clear if the PSC’s 45,200 hp refers to propulsion power or total diesel-electric power; LCC’s total diesel-electric power generation is 41.8 MW or 56,000hp).

But Charcot is a cruise ship. Surely it can’t be that good in Polar ice?

Charcot at Sea

Furthest South: Le Commandant Charcot was the first ship in the world to reach 78°44.3’ South in the Bay of Whales in the Ross Sea. The Bay of Whales was Amundsen’s departure point for his expedition, the first to reach the South Pole.

Assisting in the South: In February 2022, Le Commandant Charcot assisted the RRS Sir David Attenborough in its attempt to deliver critical science cargo in support of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration. Although the Attenborough was forced to turn back after Charcot left, this is a good example of its capabilities:

A three nmi channel was opened up in three hours; Le Commandant Charcot made the initial opening by sailing astern, with RRS Sir David Attenborough following behind, working to widen the channel.

Once the Ponant vessel departed for its next destination, sea ice conditions were against RRS Sir David Attenborough which had to turn back from its location, close to its intended depot site.

Assisting in the North: In July 2022, Charcot assisted the Norwegian Polar Research Vessel Kronprins Haakon as it approached the North Pole:

According to Ponant, the French company which operates the cruise ship, the two vessels’ captains coordinated the encounter ahead of time. In what is likely a first in the Arctic, the cruise ship opened up a channel in the ice and “escorted” the Haakon which followed behind en route to the pole.

Scientific Research Capability

For those of you interested in polar research, I’d like to note that Charcot contains 100m2 of research space, including a wet lab, a dry lab, and a computer server room. During her first two years of operations, Charcot hosted ninety-six scientists from around the world who completed thirty-four different research projects. In addition, Charcot carries a FerryBox which constantly analyzes seawater for dissolved oxygen, temperature, salinity, CO2 and pH. As she has sailed more than 120,000 nm with significant time at both poles, the FerryBox has collected significant amounts of data. And because Charcot will run mainly the same routes, the gathered data will be able to show changes over time to these key parameters.

And yes- Charcot can embark a helicopter.

“The Most Capable Icebreaking Vessel Under a NATO Flag is the French Cruise Ship Le Commandant Charcot”

This quote, by Rasmus Nygaard of the Danish Naval Architect firm KNUD E. HANSEN, appeared in a recent Polar Journal article. Is it true? The U.S. Coast Guard often says that Polar Star is the most powerful non-nuclear icebreaker in the world.

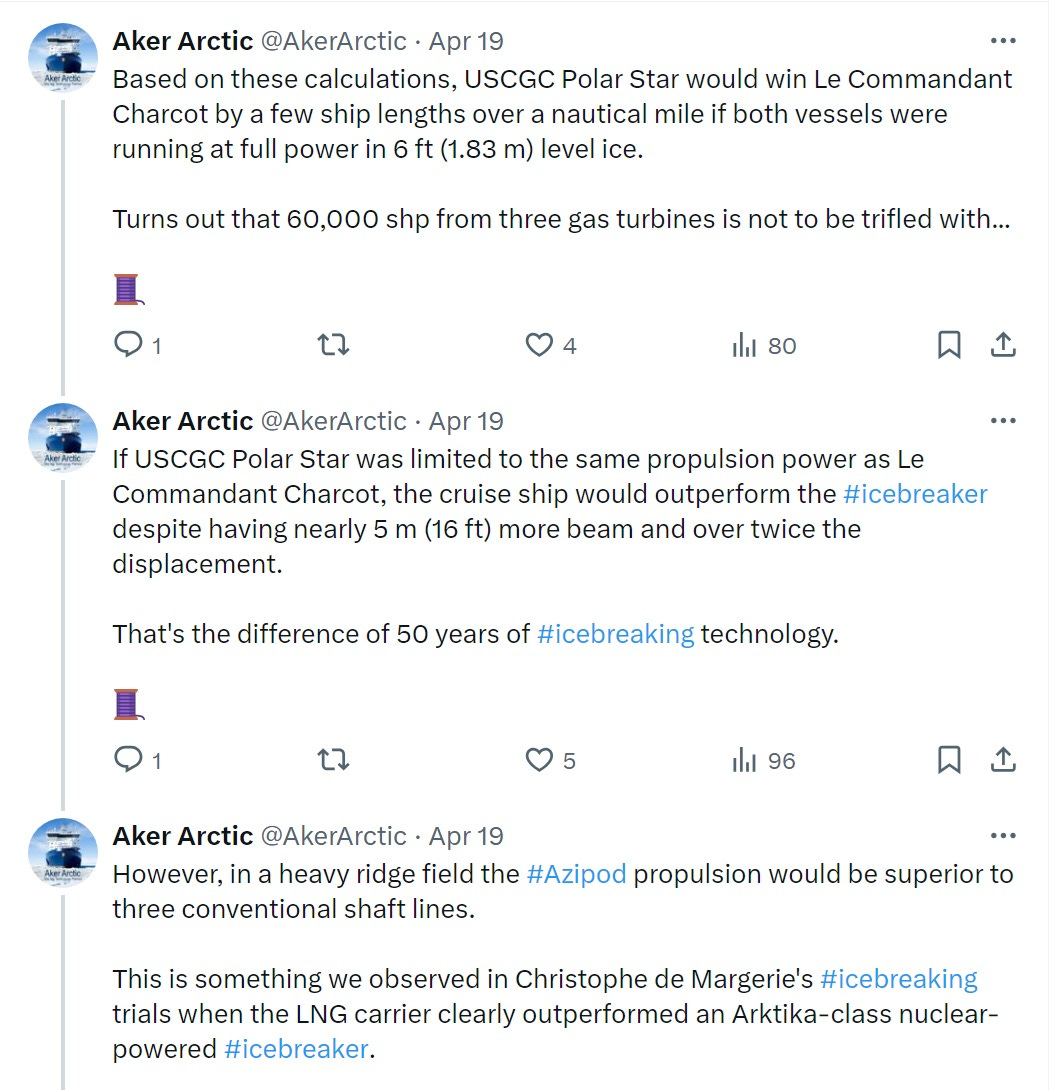

Note that the quote says most capable, not most powerful. Polar Star still holds that title. Some folks over at Aker Arctic did some back-of-the envelope estimates after this article surfaced to see how Charcot and Polar Star compare in icebreaking:

Timeline summary:

Le Commandant Charcot was a new, complex design that took Aker Arctic and its partners longer than normal (Polaris, for example, took less than three years from design contract award to delivery). Assuming a January 1, 2016 design start (all I know is early 2016), it was under six years from start until the Le Commandant Charcot reached the North Pole.

Final Thoughts: Something Must Change

In a way, it is unfair to compare Charcot’s timeline with the PSC. The U.S. Government procurement system is driven by law, politics, and a bid process that rewards the “Lowest Price Technically Acceptable” offer. As discussed during the recent Subcommittee Hearing, this creates powerful incentives for shipbuilders to ‘best case’ their bids, resulting in unrealistic time and cost estimates. The bidders pretend their bid is realistic, and the decision makers pretend to believe it. Or that they can modify it into what they really want, once the program is funded. And we know how that goes.

Private organizations like Ponant, on the other hand, can find the best suited designers and shipyards to build their ships, and by separating the design and build contracts they can be sure that the shipyard sees the mature design before they agree to build it. Sometimes, the designer can modify the design slightly to ensure the selected yard is comfortable with the requirements, avoiding the PSC’s EQ-47 problem. I could- and will- write an entire article on the different design processes used in private and government programs.

I submit that Charcot’s design and construction can serve as a model for how to successfully build a complex icebreaker. Yes, there would need to be a policy change, or a change in political will, to follow that model. But this comparison calls out for such a change if the United States intends to accomplish its required missions in the Arctic and Antarctic.

Recall that VT Halter and TAI’s bid for the PSC competed against a bid made by Fincantieri, Vard, and Aker Arctic (through Fincantieri’s U.S. subsidiary). Yes, the players behind Charcot also wanted to build the PSC. Even with the constraints of the existing procurement system, it doesn’t take much imagination to see how things might have come out differently.

I fully recognize that the United States needs a revitalized maritime industry. We need to build merchant ships, submarines, aircraft carriers, destroyers, cutters, and a whole host of other vessels while improving our ability to maintain and repair such vessels. Perhaps using our limited resources to build complex, niche vessels is not the best strategic use of our existing maritime capability. The coming Arctic Security Cutter program may be a chance to partner with foreign experts in order to acquire vessels faster while increasing our overall national industrial capability to build ships.

In the coming weeks we will look at the laws and regulations concerning foreign involvement in U.S. Navy and Coast Guard shipbuilding and will consider in some detail what a foreign partnership could look like. I’ll also address the debate on whether the U.S. Coast Guard’s icebreaking cutters need to be MILSPEC. And I haven’t forgotten that I promised to look into Bollinger’s problems with the EQ-47 alloy.

Thanks for reading. If you like what you’ve seen, press the heart and subscribe to make sure that you never miss an update. Consider sharing with a friend or fifteen; it takes me some time to research and write these articles, so I’m happy to see them spread far and wide. It’s important to keep this conversation going.

Until next time.

All the Best,

PGR

Vard is a subsidiary of Fincantieri.

“During the concept development, Aker Arctic was responsible for everything from the main deck down wards, as well as the machinery and design of the steel hull. Stirling Design International was responsible for the upper decks and interior design, while Ponant provided the guidelines for the development and ensured that everything met their requirements. Vard joined the design team during the contract negotiations.” -Aker Arctic

There is more footage in the French versions (you can turn on subtitles in English), although I have yet to find the full episode available anywhere, or any info on when it next airs, except that it will be airing again in Finland this July. If you manage to find it elsewhere, let me know.

This is a very different experience than on the older icebreakers that relied on football-shaped hulls to break the ice. It is that hull shape that helped the U.S. Coast Guard’s Polar Star to earn the nickname The Polar Roller.

Great article Pete. It’s pretty clear that perhaps we need to tweak our processes in order to achieve better results and I’m all for plagiarism if what we are copying will meet our needs.

Well, sweet. If the USCG is requiring a "parent design" process for its new icebreakers, I have an *outstanding* idea for a prime stud here...