Baltic Sea Icebreaking Update

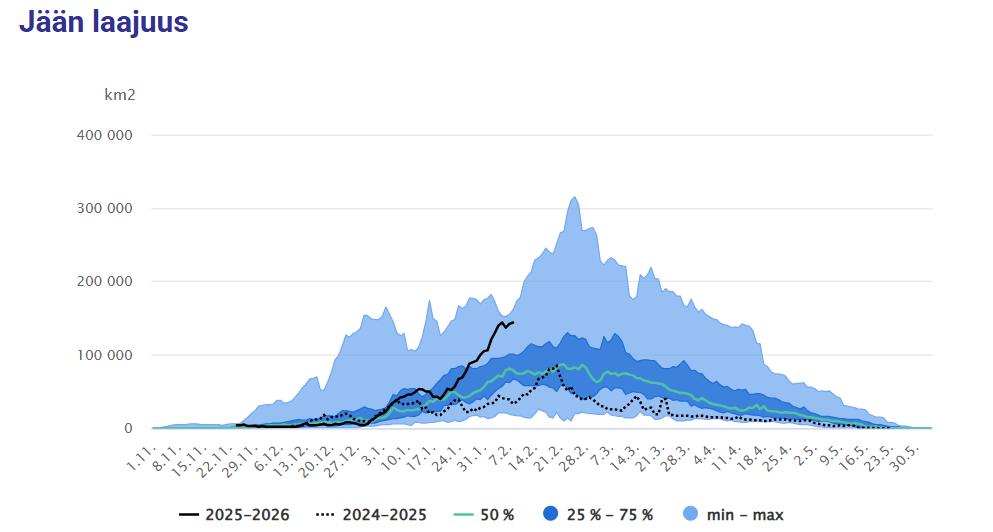

Ice coverage is above the recent average for this time of year with several weeks still remaining until peak ice, keeping icebreakers very busy.

The 2025-2026 icebreaking season kicked off in late November, when the first restrictions came into force in the Bay of Bothnia (Northern Gulf of Bothnia). By early January, Baltic Sea ice coverage had surpassed both last season’s extent and the 2007-2022 median extent for the same date.

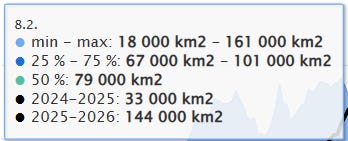

Earlier this week, ice coverage was already ahead of the 75% mark, with 144,000 km² of the Baltic Sea (total area 420,000 km²) already covered with ice.

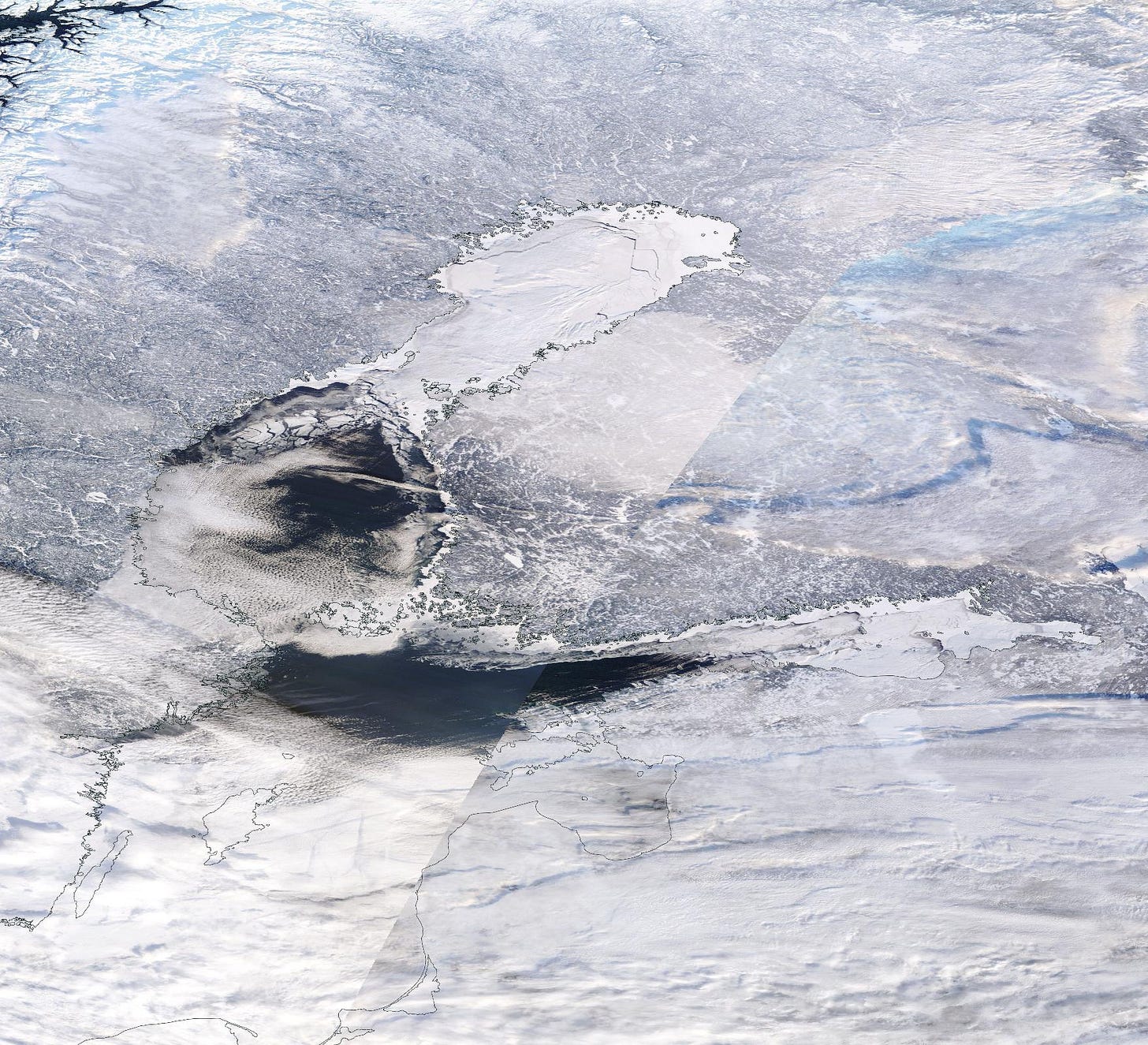

Here is what this looks like in practice:

Source: Google Earth1, Finnish Meteorological Institute.

You can see three primary areas of concern: the Gulf of Bothnia, the Gulf of Finland (between Finland, Estonia, and Russia), and the Gulf of Riga.

The sea ice extent last reached this level in the 2012-2013 icebreaking season, which peaked at 177,000 km². The current coverage already places the 2025-2026 season in the average category (which is based on peak ice) with several weeks remaining before the normal peak:

< 115,000 km²: mild season

115,000 km² ≥ average season > 230,000 km²

230,000 km² ≥ severe season > 345,000 km ²

≥ 345,000 km²: extremely severe season

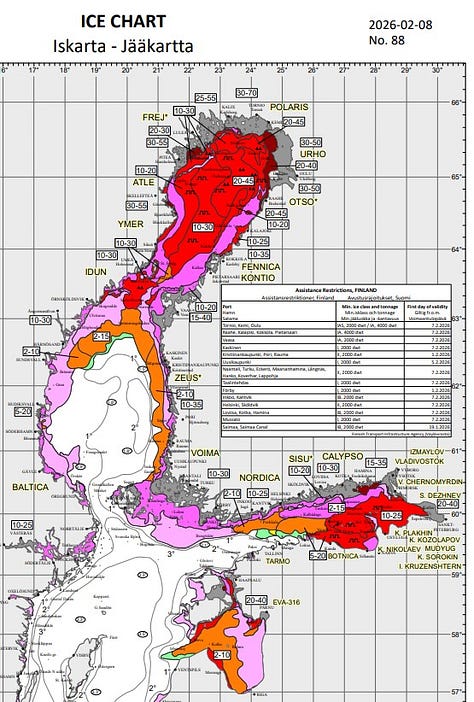

The Ice Chart above shows icebreaker names highlighted in yellow. Let’s take a close look at these icebreakers, nation by nation:

Finland: All Icebreakers are at Sea

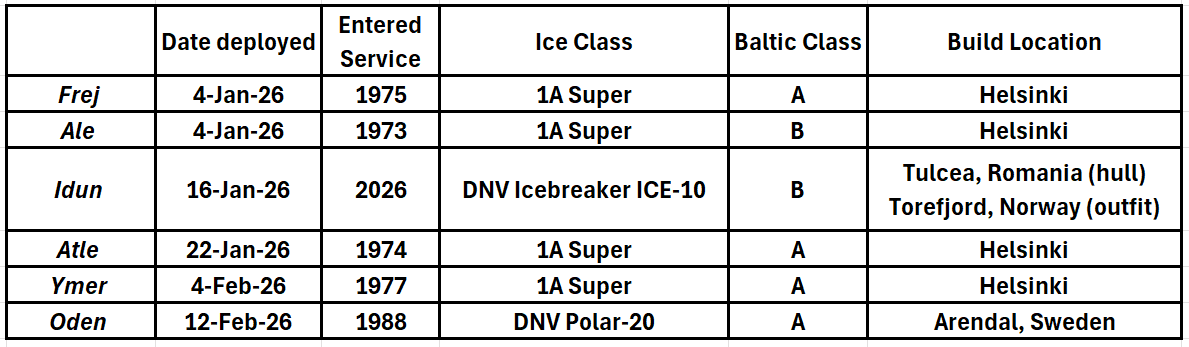

Icebreaking operations began with the icebreaking tug Zeus, owned by Alfons Håkans, heading to sea in late November. Since then, Arctia, the state-owned company that operates Finland’s icebreakers, has deployed its icebreakers as follows:

Note: The first Finnish icebreaker built to a specific classification society standard was Fennica in 1993, which was designed and built as a DNV Polar-10 Icebreaker. Before then, icebreakers were designed and built to handle their specific mission requirements. The older vessels are often referred to as 1A Super under Finnish-Swedish rules, but those requirements are for merchant vessels and relate to the fees charged for icebreaking services, not icebreaking capability.

Otso, Fennica, and Nordica were later classified under the IACS Polar Class rules, and Polaris was designed and built to them.

Bottom line: The older icebreakers have hulls strengthened for heavy icebreaking in the Baltic Sea, but are not designed to any specific ice class. They are certainly stronger than 1A Super requirements.

Otso, Fennica, Polaris, Urho and Kontio are operating in the Bay of Bothnia. Zeus assists in the Bothnian Sea and the Kvarken. Voima assists in the Archipelago Sea and the Bothnian Sea. Sisu, Nordica and Calypso are assisting in the Gulf of Finland.

Calypso is an ice-strengthened tug fitted with a detachable icebreaking bow, Saimaa.

Those that have followed Finnish icebreaking for some time might have noted that this is a different deployment order than in the past. That is because of a new icebreaking contract that allows the smaller icebreakers to deploy first, instead of Otso as has been normal in the past. You can see that the C and B class icebreakers deployed first. Here is an explanation of the differences between A and B class from the EU’s WINMOS III project webpage:

The assistance icebreakers operating in the Baltic Sea can be divided into large icebreakers (A-class) that can perform in all ice conditions, including the harshest conditions encountered in the northernmost Bay of Bothnia during severe winters, and smaller (B-class) icebreakers that are mainly used in the Gulf of Finland and Sea of Bothnia. The main difference in assistance capability between A-class and B-class icebreakers is mainly the width of the channel that the icebreaker breaks. This is an important difference since merchant vessels have varying beams. The wider the channel, the easier it is for the merchant vessel to follow.

C Class are icebreaking tugboats.

The last time all of Finland’s icebreakers were deployed was during the 2023-2024 icebreaking season. That was an average season, but it is not the ice extent alone that affects the requirement for icebreakers. Fluctuations in temperature and high winds can create difficult icebreaking conditions during mild seasons, as the wind pushes drifting pack ice against land and other ice floes to create challenging ridges. This is what drove all icebreakers to sea during the milder 2023-2024 season (peak ice of 135,000 km ²).

Let’s take a look at the rest of the Baltic.

Sweden: All Icebreakers at Sea

Note: Same as with Finnish icebreakers, the older icebreakers have hulls strengthened for heavy icebreaking in the Baltic Sea, but are not designed to any specific ice class. They are certainly stronger than 1A Super requirements.

Frej and Oden are assisting vessels in the Bay of Bothnia, while Atle, Idun, and Ymer operate in the Gulf of Bothnia. Ale is working in Vänern, the largest lake in Sweden.

The Swedish Maritime Administration is also using its two Buoy and Lighthouse support vessels, Scandica (1983) and Baltica (1982), to break ice. Baltica is operating in the Southern Sea of Bothnia, and Scandica is working in Vänern (along with Ale).

Note that Oden, which operates as a polar research vessel, is supporting domestic icebreaking operations. For the past few years, Oden has been conducting Arctic research. Last August, Oden reached the North Pole for the eleventh time, as I noted here. Previously, the U.S. National Science Foundation chartered this unique icebreaker to support Operation Deep Freeze, the re-supply of McMurdo Station in Antarctica, when no U.S. icebreakers were available. However, the Swedish Maritime Administration now requires that Oden be available for domestic icebreaking during the Northern Hemisphere winter (Antarctic summer).

Earlier this week, the Swedish Maritime Administration warned that its icebreaking resources were strained, resulting in some closures and longer wait times:

In Kalmarsund, the difficult ice situation has caused the Swedish Maritime Administration to decide to cancel the fairway for traffic, which means that the ships going to Kalmar, Mönsterås or Oskarshamn are allowed to go around Öland.

“We are doing our utmost to secure the icebreaking, but there will be extended waiting times. We are now initiating a closer dialogue with the business community to achieve the best possible situation and ensure goods deliveries to Swedish ports,” says Fredrik Backman. (Machine translated via Microsoft)

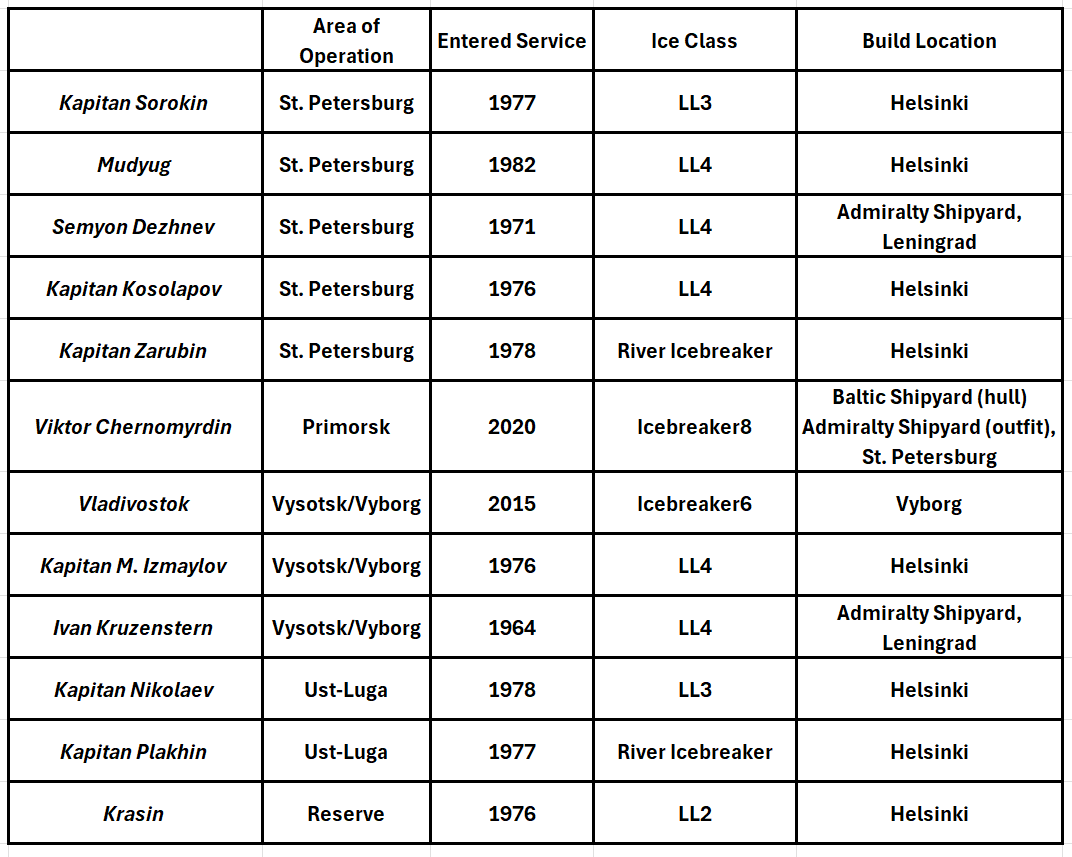

Russia: Eleven Icebreakers in Operation

According to the Rosmorport website, Russia has twelve icebreakers available in the Baltic Sea this season. Here is a table of those vessels, including their area of operation and some other key information:

Note: The classification rules used by the USSR and Russia have changed over the years. In the older set of rules for icebreakers, LL4 is the lowest classification, with LL1 being the highest2. The more modern sets of rules use icebreaker6 through icebreaker93, again lowest to highest. For more information on LL and icebreaker rules, see the footnotes.

Some reader might recognize Krasin from her support of Operation Deep Freeze:

For the past two Antarctic summer seasons (2004-2005 and 2005-2006), unusually heavy ice conditions necessitated use of two heavy icebreakers for the McMurdo break-in. During both operations, the POLAR SEA was in dry dock and was not mission capable. NSF was forced to contract for the services of the Russian icebreaker KRASIN, operated by the Far East Shipping Company (FESCO). During Operation Deep Freeze 2004-2005, the POLAR STAR was assisted by the KRASIN; during the 2005-2006 break-in, the KRASIN was hired to break the channel to McMurdo Station and the POLAR STAR was on “standby” in port in Seattle to assist the KRASIN if needed. During the 2005-2006 mission, the KRASIN lost a propeller blade, and the POLAR STAR was sent to help with the resupply. The POLAR STAR arrived in McMurdo Sound after a rapid, 23-day transit; however, NSF decided it was not necessary to utilize the POLAR STAR to assist in the resupply because the KRASIN was able to escort the tanker and cargo ship to the pier.

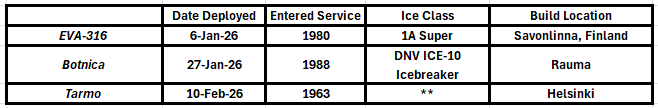

Estonia: All Three Icebreakers Underway

According to an Estonian news story from 10 February:

Estonia’s icebreakers have freed over 50 vessels from the pack ice hemming in Estonia’s coastlines and shipping lanes since the start of the year.

Two state-operated vessels, the Botnica and the EVA-316, are at work in the Gulf of Riga and the area around Pärnu, as well as the bulk of Estonia’s islands; another ship, the 60-year-old Tarmo, is heading to Muuga Bay, just east of Tallinn, on the Gulf of Finland.

The Tarmo will set out late tonight, Tuesday, as the first icebreaking orders must be fulfilled by noon Wednesday, “Aktuaalne kaamera” reported. (machine translation by Microsoft)

**Tarmo, like the older Finnish icebreakers mentioned earlier, was not built to specific ice class rules. While Finland and Sweden now consider their older icebreakers 1A Super, Estonia does not use an ice class designation for Tarmo. Like the other Finnish vessels, she is purpose-built for icebreaking and is stronger than a 1A Super ice class suggests.

EVA-316 began life in Finland as the buoy tender Lonna. Purchased in 1995 by the Estonian Transport Administration, she was converted in 2004 into a multi-purpose vessel in a substantial conversion that included adding an icebreaking bow.

The Port of Tallinn purchased Botnica from Finland in 2012; Botnica was last in the news assisting a vessel that had run aground in the Northwest Passage.

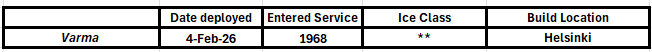

The Estonian Transport Administration purchased Tarmo from Finland in 1993. Tarmo’s sister ship, Varma, was transferred to Latvia in 1994.

Latvia: Icebreaker Varma at Sea

According to the Latvian news site Jauns, the Icebreaker Varma went to sea to begin icebreaking on February 4th. The last time Varma went on an icebreaking mission was during the winter of 2018.

**See note on Tarmo above.

Varma, delivered in 1968, was built in Finland by what is now known as Helsinki Shipyard. She was transferred to Latvia in 1994.

Germany

German-built multi-purpose vessels are also participating in icebreaking operations. Arkona began operating along Germany’s Baltic Coast:

The ice cover on the coastal waters in Western Pomerania is becoming increasingly thicker. Because of the persistent sub-zero temperatures, the Baltic Sea Waterways and Shipping Authority has used the multi-purpose ship "Arkona" to break ice. The aim is to keep the important shipping lanes open for commercial shipping.

Particularly affected by the ice is the eastern approach to Stralsund, where the ice cover is much more pronounced in places. Experts from the Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency expect the ice to continue to increase in the coming days. The icebreaker used, the "Arkona", is considered the most powerful German icebreaker in the Baltic Sea and can handle ice thicknesses of up to half a meter.

(Machine translation by Microsoft)

Needing a ship with more capability, Germany swapped Arkona with Neuwerk, a larger and more capable multi-purpose vessel that had been operating in the North Sea. According to a February 11th German news report:

The terminal operator had already cleared the port of ice with several tugboats. A powerful ship was needed for the fairway. The "Neuwerk" has come from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea for this purpose. It is almost ten meters longer and more powerful than the "Arkona" stationed in the Baltic Sea. This means that the "Neuwerk" is better able to break thick ice. The ship is expected to remain on site for about a week, the WSA said. The "Arkona" was temporarily transferred to the North Sea for this purpose. (Machine translation by Microsoft)

Thoughts and Comments

Ice Conditions

Ice coverage is not the only factor in determining the severity of an icebreaking season. The 2023-2024 saw less than average ice coverage, yet all of Finland’s icebreakers were deployed. As I described it then:

Maximum sea ice is actually a poor predictor of icebreaking requirements, as fluctuations in temperature and wind speed play a very large role. The most challenging conditions are created by drifting pack ice which, pushed by the wind, forms challenging ridges along the coast.

Finland’s eight icebreakers (operated by Arctia) and two icebreaking tugs, chartered from Alfons Håkans, are purposely designed to assist vessels in the challenging ice conditions and shallow, narrow channels in the Gulf of Bothnia and Gulf of Finland.

One interesting factor is just how far south the ice coverage developed this year. As mentioned earlier, Latvia last deployed its icebreaker in 2018. Ice conditions in the regions of the Baltic are very hard to predict, so we’ll just have to see how it turns out.

Aging Icebreakers

To put it simply, the Baltic icebreaking fleet is aging. Three out of eight Finnish icebreakers, four out of six of Sweden’s icebreakers, two of Estonia’s three icebreakers, Latvia’s sole icebreaker, and ten out of twelve of Russia’s assigned icebreakers are more than forty years old. (That’s twenty out of thirty, or nineteen out of twenty-nine if you exclude Estonia’s multi-purpose vessel)

Finland, Sweden, Estonia, and Russia are all working on updating their fleets.

Finland is starting by replacing the 1954-built Voima. The new design was just selected, and the project should soon move to the tendering stage. Construction start is planned for 2027 with delivery in 2029. I’ll be writing more on this soon.

Sweden had hoped to have two new icebreakers under construction by now, but funding challenges reduced the order to one, and the contract award, made to Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), is currently under legal challenge. There is also some discussion of building a new research icebreaker to replace Oden, but it is far from clear how such a vessel could be financed.

Estonia is working with Finland to replace the aging Tarmo.

Russia has roughly twenty icebreakers under construction, but many of those programs are struggling due to sanctions and other difficulties. I’ve written about some of this before and am currently working on a more comprehensive look at Russia’s icebreakers.

Finnish expertise

If you exclude the tugs and multi-purpose vessels, this article references twenty-nine icebreakers. Of those twenty-nine, twenty-three were built in Finland (twenty at Helsinki Shipyard, three at what is now Rauma Marine Constructions), four in Russia, one in Sweden, and one in Romania/Norway. Those numbers say quite a bit.

Considering Russia’s Icebreakers

Russia is building powerful nuclear icebreakers, but it will also need to replace a large number of icebreakers that serve the Baltic Sea and other key regions. Of the twelve Russian icebreakers mentioned in this article, ten are more than forty years old, and eight of them were built at Helsinki Shipyard. This trend continues across much of Russia’s icebreaking fleet— many of the vessels are old and require replacing. Because of sanctions, Russia must now rely on its own shipyards, making this an even more difficult challenge.

A thought on Ice Class

I’ve included the ice class of these vessels in an attempt to illustrate the challenge of comparing older icebreakers with each other and in comparing the older icebreakers with modern vessels. I’d be happy to answer questions about this.

Thanks for reading. Be sure to like, subscribe, and share. There’s much more in the works.

All the Best,

PGR

Further reading:

Google Earth map contains data from Google, Landsat / Copernicus, Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, IBCAO, GeoBasis-DE/BKG (©2009), U.S. Geological Survey.

Here are the LL icebreaker classification descriptions from 1995 Russian Maritime Register of Shipping Rules for the Classification and Construction of Sea-Going Ships:

LL1— intended for all kinds of icebreaking operations in the arctic seas on coastal routes and shore ice belt routes in high latitudes all the year round and capable of forcing the way in compact ice field over 2 m thick. The total shaft power is 47807 kW and over.

LL2— intended for all kinds of icebreaking operations in the arctic seas during the summer period and for operation on coastal routes during the winter period, and capable of forcing the way in compact ice field less than 2 m thick. The total shaft power is 22065-47807 kW;

LL3— intended for all kinds of icebreaking operations in the nonarctic freezing seas, in shallow waters and mouths of rivers flowing into the arctic seas during the winter period without assistance as well as for operation on coastal routes in the arctic seas under convoy of icebreakers of higher category all the year round, and capable of forcing the way in compact ice field up to 1,5 m thick. The total shaft power is 11032-22065 kW;

LL4— intended for all kinds of icebreaking operations in harbour and roadstead water areas without assistance all the year round as well as for operations in the non-arctic freezing seas under convoy of icebreakers of higher category during the winter period, and capable of forcing the way in compact ice field up to 1 m thick. The total shaft power is under 11032 kW.

Icebreakers of the above ice classes have the following tentative service characteristics:

Icebreaker6 — intended for ice breaking operations in harbour and roadstead water areas as well as in freezing seas where the ice is up to 1,5 m thick. Continuous motion capability in unbroken ice up to 1 m thick. The total shaft power not less than 5,5 MW;

Icebreaker7 — intended for ice breaking operations in the arctic seas on coastal routes during winter/spring navigation in ice up to 2,0 m thick and summer/autumn navigation in ice up to 2,5 m thick; in non-arctic freezing seas and mouths of rivers flowing into arctic seas in ice up to 2,0 m thick. Continuous motion capability in unbroken ice up to 1,5 m thick. The total shaft power not less than 11 MW

Icebreaker8 — intended for ice breaking operations in the arctic seas on coastal routes during winter/spring navigation in ice up to 3,0 m thick and summer/autumn navigation without restrictions. Continuous motion capability in unbroken ice up to 2,0 m thick. The total shaft power not less than 22 MW;

Icebreaker9 — intended for ice breaking operations on coastal routes in arctic seas during winter/spring navigation in ice up to 4,0 m thick and summer/autumn navigation without restrictions. Continuous motion capability in unbroken ice over 2,0 m thick. The total shaft power not less than 48 MW.

You might enjoy reading "Dead Reckoning" my new book which has some good icebreaking stories.

Available on Amazon, Barnes & Knoble, paperback with Hard bound in about two weeks.

Meanwhile I and a group of friends are cranking up a new ship building yard in USA