Canada's National Shipbuilding Strategy, the Multi-Purpose Icebreaker, and the U.S. Coast Guard

Perhaps we can learn something about the MPI by taking a close look at why Canada is building the vessel.

Those of you who follow icebreakers or the U.S. Coast Guard closely have probably read or heard about Canada’s Multi-Purpose Icebreaker (MPI) design. Seaspan, the Canadian shipyard that owns the design, has been marketing the MPI design for the U.S. Coast Guard’s Arctic Security Cutter (ASC) heavily for the past few months. Seaspan itself has just recently completed functional design of the MPI and plans on building them for the Canadian Coast Guard in the coming years. They have no capacity to build any additional vessels themselves for at least the next decade so have been looking for partners.

On July 19th we learned the Seaspan was teaming up with the Finnish design firm Aker Arctic and Rauma Marine Constructions (RMC), a Finnish shipbuilder, to build two MPIs in Finland for the U.S. Coast Guard. An unspecified U.S. shipyard would be involved, gaining experience so that subsequent vessels could be built wholly in the USA. On July 29th we learned that Bollinger was the previously unnamed U.S. shipyard.

I have many thoughts on this proposal. But those will have to wait for another day as today I want to fill an important gap in the discussion. Most discussions of the design are superficial if they even occur, noting that the vessel meets or exceeds the parameters listed in the U.S. Coast Guard’s ASC Request for Information (RFI). But that RFI does not discuss how the ASCs will be used in any detail. Today, we will look at what the MPI is designed to do for the Canadian Coast Guard. To better understand its role, we are going to take a brief look at Canada’s current icebreaker fleet and their planned recapitalization under the National Shipbuilding Strategy.

The Canadian Coast Guard

The Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) falls under Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Unlike its U.S. counterpart, the CCG has no law enforcement or defense responsibility1. According to their website, the CCG supports six major programs:

Aids to Navigation

Marine Environmental and Hazards Response

Icebreaking Services

Marine Communications and Traffic Services

Search and Rescue

Waterways Management

The Canadian Coast Guard icebreaking program makes sure that marine traffic moves safely through or around ice-covered waters.

From December to May, icebreakers and hovercrafts operate along Canada’s east coast from Newfoundland to Montréal and in the Great Lakes. From June to November, icebreakers provide services in the Arctic.

Canadian Coast Guard ice operations centres task our fleet of icebreakers and guide the movement of marine traffic through ice. With the support of the program, most Canadian ports are open for business year-round.

To support this, the CCG currently operates nineteen icebreakers of varying capability2. Add in the ice-capable patrol vessels operated by the Royal Canadian Navy, and you get twenty-four vessels.

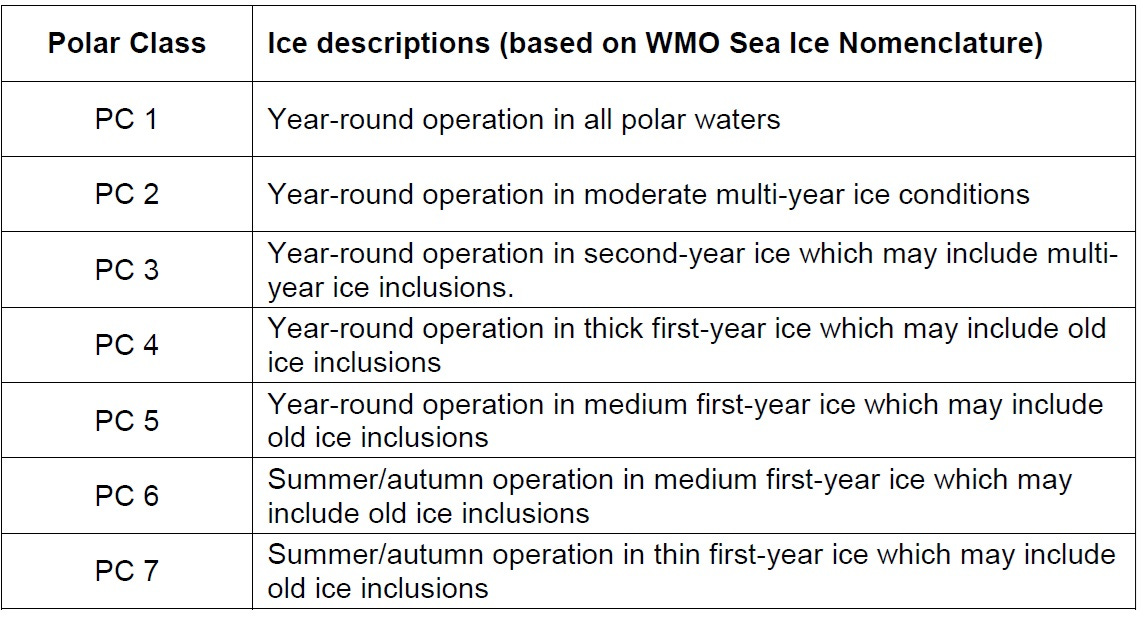

As we look at the fleet in detail, note that terms used are specific to Canada. For example, a Canadian ‘heavy’ icebreaker is different in capability from a U.S. Coast Guard ‘heavy’ icebreaker. This is one of the reasons that I prefer other means of classification. Today we can use Polar Class3 (PC), as it is standard across the world. However, the vast majority of Canada’s icebreaking fleet predates the adoption of the IACS Polar Class Rules. Sometimes equivalent PC can be used; for example, the U.S. Coast Guard ‘Heavy’ Icebreaker Polar Star is PC2-equivalent, while Canada’s Heavy Icebreaker Louis S. St. Laurent and the U.S. Coast Guard’s Medium Icebreaker Healy are both PC4-equivalent4.

Canada’s Current Icebreaking Fleet

(Number of vessels of each type in parenthesis)

Heavy Icebreakers (2):

CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent: Delivered in 1969, this storied icebreaker has had her service life extended several times5 and is due for replacement. Built before the IACS Polar Class standards came into effect, she is considered equivalent to a modern PC 4 icebreaker.

CCGS Terry Fox: Delivered in 1983 as a commercial icebreaker, she was leased to the CCG in 1991 to cover an extended maintenance period for St-Laurent. Following the lease, she was purchased by the CCG and continues in service today. Estimates of her equivalent Polar Class vary between PC3 and PC4.

Medium Icebreakers (7):

Pierre Radisson-class (4): Delivered between 1978 and 1988, these vessels operate in the Arctic Ocean during the summer months patrolling, icebreaking and conducting research missions. The first three vessels of the class are considered PC4 equivalent, with the fourth (an improved version) considered PC3.

Interim icebreakers (3): Consists of three commercial icebreakers purchased from Viking Supply Ships and converted by Davie for operation as CCG icebreakers6. Originally delivered in 2000/2001, these PC4 ships entered CCG service between 2019 and 2023.

Light Icebreakers (10):

Note: Drafts included for later comparison with MPI.

High Endurance Multi-Tasked Vessels (7):

CCGS Griffon: A light icebreaker and buoy tender that entered service in 1970. Draft: 15 ft 6 in.

Martha L. Black-class (6): Light icebreaker and buoy tenders that entered service between 1986 and 1987. Draft 19 ft 8 in.

Medium Endurance Multi-Tasked Vessels (3):

Samuel Risley-class (2): Light icebreakers/buoy tenders delivered in 1985-1986. Draft 17 ft 1 in.

CCGS Judy LaMarsh: Originally built as a shallow-water icebreaking tug Mangystau-2 in 2010, she was acquired by the CCG in 2021 and converted for use. Draft: 9 ft 10 in.

Royal Canadian Navy:

Harry DeWolf-class Arctic Offshore Patrol Ships (5): Five of six planned ships have been delivered since 2021, with the sixth expected later this year. These PC5 vessels are lightly armed and used to patrol Canadian waters and its EEZ. Two additional vessels are planned for the Canadian Coast Guard, but they will not be armed.

Harry DeWolf armament:

1 x BAE systems Mk 38 Mod 3A 25mm machine gun system

2 x crew served M2 .50cal mounts

This is essentially the same as on the U.S. Coast Guard’s 400 ton Sentinel-class Fast Response Cutter

For a closer comparison, the U.S. Coast Guard’s planned Heritage Class Offshore Patrol Cutters, which are slightly smaller than the AOPS (4500 long tons vs 6500 for the AOPS) have the following:

1 x Mk 110 57mm gun

1 x BAE systems Mk 38 Mod 3 25mm machine gun system with 7.62mm coaxial gun

2 x stabilized M2 .50cal machine guns

4 x crew served M2 .50cal machine guns

Current Fleet Summary

Those just learning about Canada’s fleet may be surprised that its vessels are less capable than the U.S. Coast Guard’s polar icebreakers. This is driven by mission, with the CCG mostly ensuring safe navigation in seasonably icy waters while the U.S. Coast Guard supports more challenging missions such as the resupply of the National Science Foundation’s McMurdo Station in Antarctica.

Note that the last Canadian-built icebreaker (aside from the PC5 AOPSs) entered service in 1988. Since that time, the CCG has added commercial icebreakers to its inventory through purchase and conversion but has been unable to deliver on plans for new built vessels for a number of different reasons beyond the scope of today’s article.

Today, the Canadian Government has a plan to steadily acquire ships in order to rebuild its fleet and revive Canadian shipbuilding. This plan is known as the National Shipbuilding Strategy.

Canada’s National Shipbuilding Strategy

In 2010, the government made a commitment to create jobs and equip the Royal Canadian Navy, the Canadian Coast Guard and Transport Canada with much-needed vessels. The National Shipbuilding Strategy is helping restore our shipyards, rebuild our marine industry and create sustainable jobs in Canada while ensuring our sovereignty and protecting our interests at home and abroad.

Eliminating Cycles of Boom and Bust

From the mid-1990s to 2010, Canada’s shipbuilding industry had slowed down significantly. There had not been any substantial new orders to construct vessels for many years. Compared to other countries, Canada’s shipyards were outdated and there was no easy access to equipment, supply lines and skilled workers. It was time for a new approach.In 2010, the government made the decision to support Canada’s marine industry and build vessels here in Canada. This approach, called the National Shipbuilding Strategy, is developing a sustainable, long-term shipbuilding plan that benefits Canadians and the Canadian marine industry. Through the strategy, we are revitalizing Canadian shipyards and constructing vessels for the Royal Canadian Navy, Coast Guard Canada7, and Transport Canada, here in Canada.

The strategy allows the government and the shipyards to make significant investments in Canada’s marine industry, such as developing and maintaining expertise and creating sustainable employment across the country. It brings predictability to federal vessel procurement and aims to eliminate the boom and bust cycles of vessel procurement that slowed down Canadian shipbuilding in the past.

For large vessels (greater than 1000 tons), the Canadian government partnered with three shipyards: Seaspan, Davie, and Irving. Here is the current build plan, with icebreakers in bold:

Irving:

6 x AOPS for RCN (5 delivered)

2 x AOPS for CCG

15 x River Class Destroyers for the RCN Navy

Seaspan:

3 x CCG Offshore Fisheries Science Vessels (Delivered)

1x CCG Offshore Oceanographic Science Vessel (OOSV) (just completed sea trials)

2x RCN Joint Support Ships (JSS) (under construction)

1x CCG Polar (Construction began April 2025)

16x CCG Multi-Purpose Icebreakers in three flights. First flight (6) expected to start construction in 2027

Davie

1x CCG Polar Icebreaker (Polar) (Construction to start soon)

6x CCG Program Icebreakers (PIB)

2x Transport Canada (TC) large ferries

Note: Davie was not selected as an original partner in the NSS. It signed its agreement to officially become a NSS partner only in 2023, with its first NSS contract (an initial contract for the Program Icebreakers) awarded in March of 2024. This is why it has a smaller list and has not yet delivered any vessels. However, construction on Davie’s Polar Icebreaker— for which Davie’s first and only contract was signed in March— is expected to start quite soon.

The Icebreaker Build Programs:

Two Polar Icebreakers (Davie, Seaspan):

As part of its fleet renewal plan, the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) is acquiring 2 polar icebreakers through the National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS). To deliver these vessels by the early 2030s, construction work is being done by 2 shipyards: Chantier Davie Canada Inc. and Seaspan’s Vancouver Shipyards.

These polar icebreakers will:

be Canada’s most powerful icebreakers and among the most powerful icebreakers in the world

enable CCG to operate at higher latitudes for longer periods

help the fleet better support Indigenous Peoples and other northerners

strengthen Arctic security

advance high Arctic science

improve responses to maritime emergencies

I wrote about the Polar contracts awarded to Seaspan and Davie earlier this year:

Six Program Icebreakers (Davie):

The program icebreakers will:

replace the heavy and medium icebreakers of the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) that operate in Atlantic Canada, the St. Lawrence waterways, the Great Lakes and Pacific Canada during the winter, and in the Arctic during the summer

provide aids to navigation, search and rescue, environmental response, northern resupply missions and vessel traffic services to fulfill obligations of the CCG under the Canada Shipping Act

be used to exercise Canada’s Arctic sovereignty as part of Canada’s increasingly rigorous security requirements in Arctic waters, which are becoming more accessible due to climate change

Multi-Purpose Icebreakers (Multi-Purpose Vessels) (Seaspan):

The multi-purpose icebreakers will enable the Canadian Coast Guard to carry out multiple missions, including:

icebreaking in the Arctic in moderate ice conditions

assisting with shipping and springtime flood control in the St. Lawrence waterway and Great Lakes regions

conducting missions involving search and rescue, emergency response, and security and protection

maintaining Canada’s marine navigation system, composed of approximately 17,000 aids to navigation

These ships were called “multi-purpose vessels” until March 2025.

The current plan is to build the MPIs in three flights.

The first flight of six vessels will replace the existing High Endurance Multi-Tasked Vessels and Medium Endurance Multi-Tasked Vessels.

The second flight of five ships will be different. One plan I saw says that it will be smaller, with a shorter range, and have no aviation capability. This makes sense, as the MPI is also supposed to replace a host of smaller ice-capable offshore patrol vessels— which are not classified as icebreakers—used by the CCG. As they are not icebreakers, I did not list them in the current fleet section.

The third flight of five ships will be similar to the first flight and will incorporate technological advances to reduce its carbon footprint.

NSS Overview

The new polar icebreakers will give the CCG their first real heavy icebreakers, adding to its reach in the Arctic.

The Program Icebreakers will replace Canada’s aging heavy icebreakers and medium icebreakers with purpose designed vessels to operate in Arctic conditions

The Multi-Purpose Icebreakers will replace the CCG’s aging fleet of buoy tenders/light icebreakers8 with vessels capable of summertime operation in Canada’s Arctic. This is an increase in capability because the MPIs are a big step up in capability from the vessels they are replacing (at least the first flight). According to some earlier material:

The MPV is replacing up to three classes of older ships with one platform. The target is to develop a compact ship with a multitude of operational roles. The sixteen vessels will mainly replace the Type 1100 class built in the late 70s and early 80s, often called the “work horses” of the fleet, doing the day-to-day work of supporting shipping by maintaining fairways, aids to navigation, and icebreaking.

The MPVs will also perform cargo missions, bringing supplies to northern communities, carry out search & rescue and patrol missions, in addition to icebreaking. Most of their time will be spent on the St Lawrence River, the Great Lakes, and along the Canadian East Coast. Additionally, they will have a summer Arctic mission leaving from Victoria in British Columbia and travelling north around Alaska to the Canadian Arctic.

The MPI is a big step up

The vessels the MPI is replacing are mainly Arctic Class 2 vessels. This classification goes back to an earlier Canadian regulatory regime in which a vessel’s Arctic Class limited where and when it could operate in the Canadian Arctic. The curious can find the full regulations are archived here (see schedule VIII for the class chart) and a map of the zones here. Replacing these vessels with a vessel capable of year-round operations is quite impressive.

Here are some updated capabilities provided via e-mail by Dave Hargreaves, Seaspan’s Senior Vice President for Strategy, Business Development, and Communication.

• Open water speed: 16.0 knots

• Speed in 1.0m ice: 4.0 knots

• Max ice thickness at 3 knots: 1.3m

• Range at 10 knots: 13,500 nautical miles. Note that it is about 3,000 nautical miles from Seattle to northern Alaska, so the 6,000 nm range in the RFI is likely insufficient for meaningful operations in the Arctic.

• Flight operability and deck operations in Sea State 5, compliance with NATO STANAG 4154 requirements for seakeeping

In comparing the MPI with the AOPS, he added:

These are both very capable vessels that meet the USCG requirements, however, they have very different missions. The MPI is a real icebreaker with broad capabilities to fulfill an icebreaking mission.

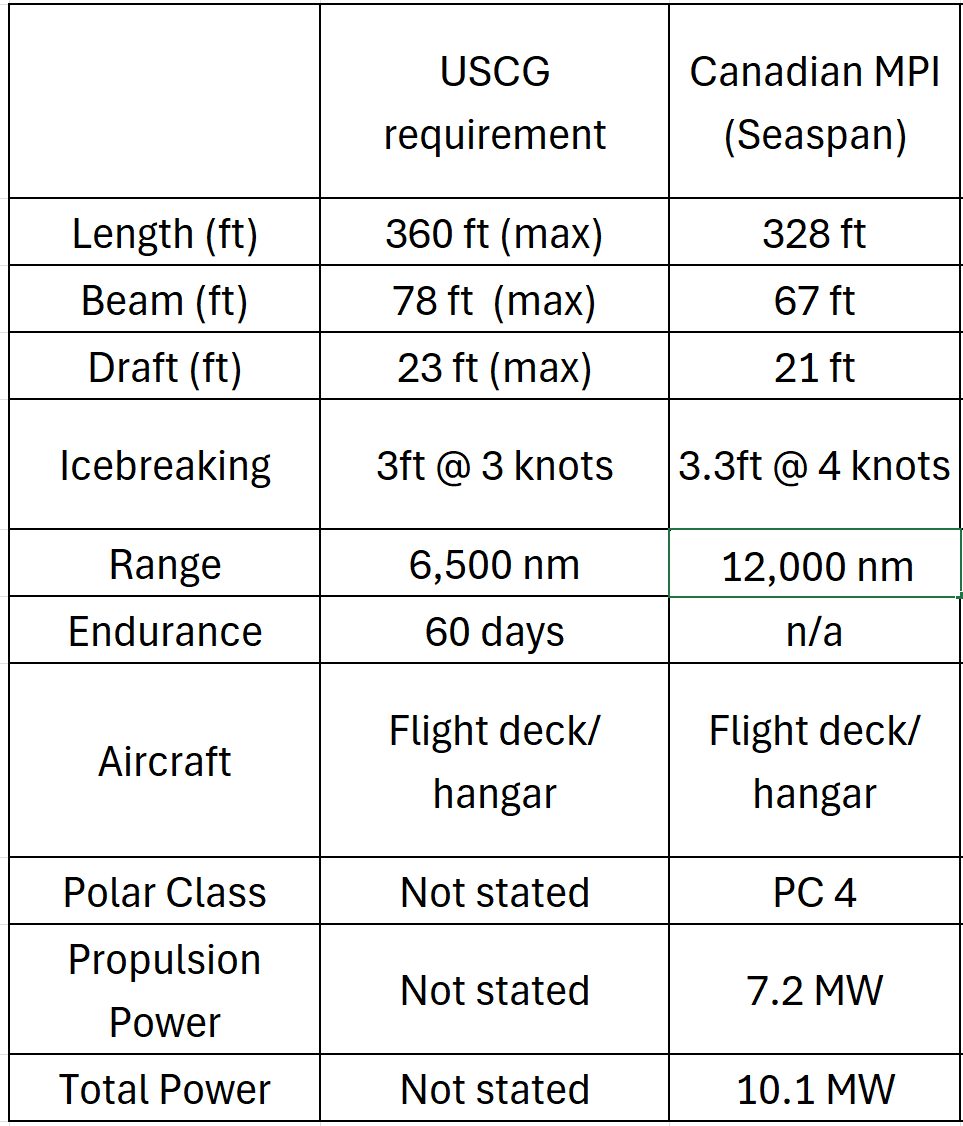

These replacement vessels for Canada’s light icebreakers/buoy tenders even meet the minimum specifications outlined in the U.S. Coast Guard’s Arctic Security Cutter Request for Information:

MPI Design Constraints:

Vessel Size:

From an Aker Arctic article:

Due to the wide variety of tasks, the long-distance mission to the western Arctic, and the fact that some of the waterways have a limited depth, the vessel needed to be compact with a shallow draught, narrow beam, high endurance, and with a large cargo capacity.

Reduced Emissions/Carbon Footprint:

The article continues:

During the design process a need arose to evaluate the future environmental impact and greenhouse gas emissions, bearing in mind that this is a long-term project.

In the end, the Coast Guard decided to update the design with an optimized version, where the ship was redesigned to allow for future alterations when alternative fuels become available.

….

A number of energy-saving devices were also evaluated. These included energy-storage devices such as battery packs; thermal storage in the form of waste heat utilisers capturing and reusing heat from the power plant; and alternative energy sources such as energy stabilizers, solar panels and wind turbines.

The aim was to evaluate the present state of the technology and how practical it would be to implement it into the design for optimal environmental efficiency.

Due to the ship’s size, a decision was made to prioritize the missions against using space for energy-saving devices at this stage. However, as the design continues to progress and spaces and weights become finalized, there is the possibility of implementing some of the options.

U.S. Coast Guard Concerns Not Listed in the RFI

Propulsion Power:

At 7.2 MW, the MPI’s total propulsion power is low compared to other ‘medium-type’ icebreakers. This is at least partly due to the constrained draft of the MPI.

With reduced size come design challenges, as described in this Aker Arctic article:

“For instance, a shallow draught means that the propulsion system components must be relatively compact to fit the hull correctly and remain submerged. However, a smaller propeller diameter provides less thrust, which is a key feature in icebreaking,” he explains.

In shallow water, the vessel’s weight control is a crucial aspect of the design. It determines the equipment selection, endurance, and crew size; every feature that adds more weight. Also, the displacement relative to the vessel’s underwater side profile area can become substantial, impacting manoeuvrability.

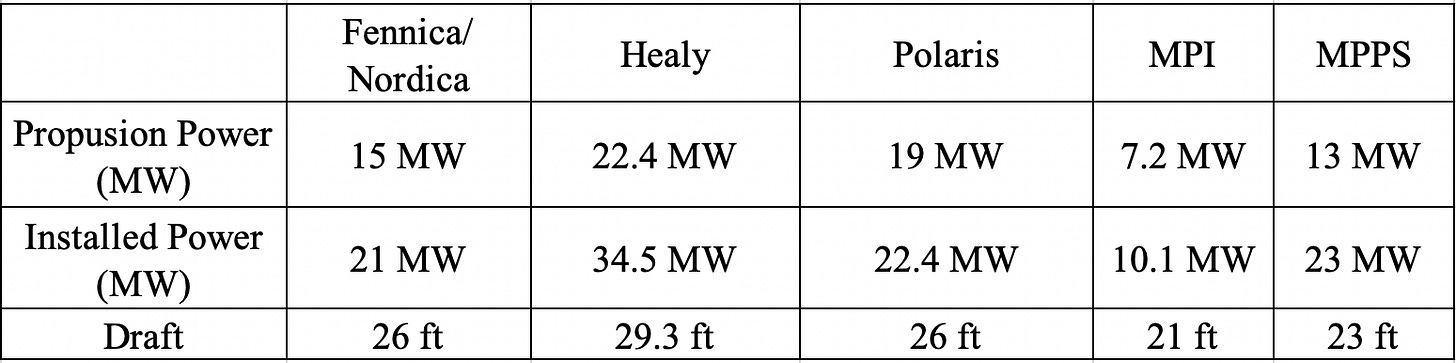

Here is a quick comparison of the MPI’s power as compared to other ships with a greater draft. Even just a few feet more can allow for more power:

Note: Early on, the MPV/MPI was described as a ‘light’ icebreaker. However, in current discussions it is being offered to fill the role of a ‘medium’ icebreaker, the Arctic Security Cutter. For that reason, I think it is fair to compare it to medium vessels with slightly more draft.

Redundant Power:

Take a look at the installed power in the above chart. This is apparently a choice borne of the desire for a lower carbon footprint expressed during the design phase. From a June e-mail exchange I had with Seaspan:

[The MPI’s capability] is achieved with just 7.2 MW of propulsion power and just over 10MW of total installed power. We believe that this makes the MPI an extremely good deal for any client, achieving similar performance to competitors designs with a smaller power and propulsion plant leading to lower acquisition cost and lifetime fuel running costs (all else being equal.)

The ship’s 10.1 MW of power comes from four diesel engines (2 x ~3500 kw and 2 x ~1500 kw). With 7.2 MW of propulsion (and 2 x 1 MW bow thrusters), there is not much reserve power. Having one (of four) diesel engines broken or down for maintenance will severely limit the ability of the vessel to conduct its missions.

For example if one of the MPI’s larger diesels were unavailable, maximum power output would be 6.5 MW— not enough for full engine power. (It may be so that the propulsion bus is separate, with the two larger diesel generators for propulsion and the smaller for ship’s loads. This wouldn’t change my perspective on redundancy).

Compare this to the redundancy on Healy. She has four generators, each capable of generating 8.64 MW, for a total of 34.56 MW . If one generator were unavailable, that still leaves 25.92 MW—enough to fully power both propulsion motors (22.2 MW) with 3.72 MW remaining for other loads.

If the ASCs are to operate independently in the Alaskan Arctic, the U.S. Coast Guard might value redundancy over efficiency.

Survivability/Crew Size

The MPI is designed to commercial cargo ship standards9. Long time readers will recall that I’ve advocated for the U.S. Coast Guard to build its own icebreakers to modern commercial standards. However, based on the U.S. Coast Guard’s perceived requirements, I specifically meant the more stringent passenger ship standards.

My opinion is based in part on a 2017 Study from the National Academy of Sciences on the Polar Security Cutter:

Because the ship will have more than 100 persons on board, some not nautically trained, application of SOLAS damage stability requirements for a passenger ship with more than 36 persons on board would be appropriate. In general, passenger ship damage stability requirements are significantly more severe than are those for cargo ships. Overall, the committee anticipates that applying international and polar damage stability requirements will result in a ship that is safer in ice conditions without having to manage the more costly and difficult-to-design changes needed to meet MIL-SPEC requirements for a ship anticipating combat.

Certain large passenger ships built on or after July 1, 2010 have to comply with the SOLAS Safe Return to Port (SRTP) requirement. This means that a ship must be capable of losing a space (up to the applicable boundary) due to fire or flooding and be able to maintain essential services. For the case of fire, it must be able to safely return to port under its own power while maintaining essential services.

In practice, meeting the SRTP requirement means placing key components in different spaces. This is not required for cargo vessels.

For additional survivability, the U.S. Coast Guard might want a vessel designed and built to passenger ship survivability standards with the additional SRTP designation.

Note also that the MPI has a complement of 50. Should the U.S. Coast Guard require a complement of 60 or more, at least some passenger ship safety standards will apply, requiring significant design modification.

Weapons and Sensors:

As mentioned earlier, CCG vessels are unarmed. Adding more than crew-served weapons would likely require a design change.

According to a recent report, the Canadian MPIs will use the SCANTLER 4603 Naval Air and Surface Surveillance Radar. You can find the brochure for the system here. I don’t know much about it, it is not in standard U.S. usage. I would imagine the U.S. Coast Guard would want to use its own standard equipment.

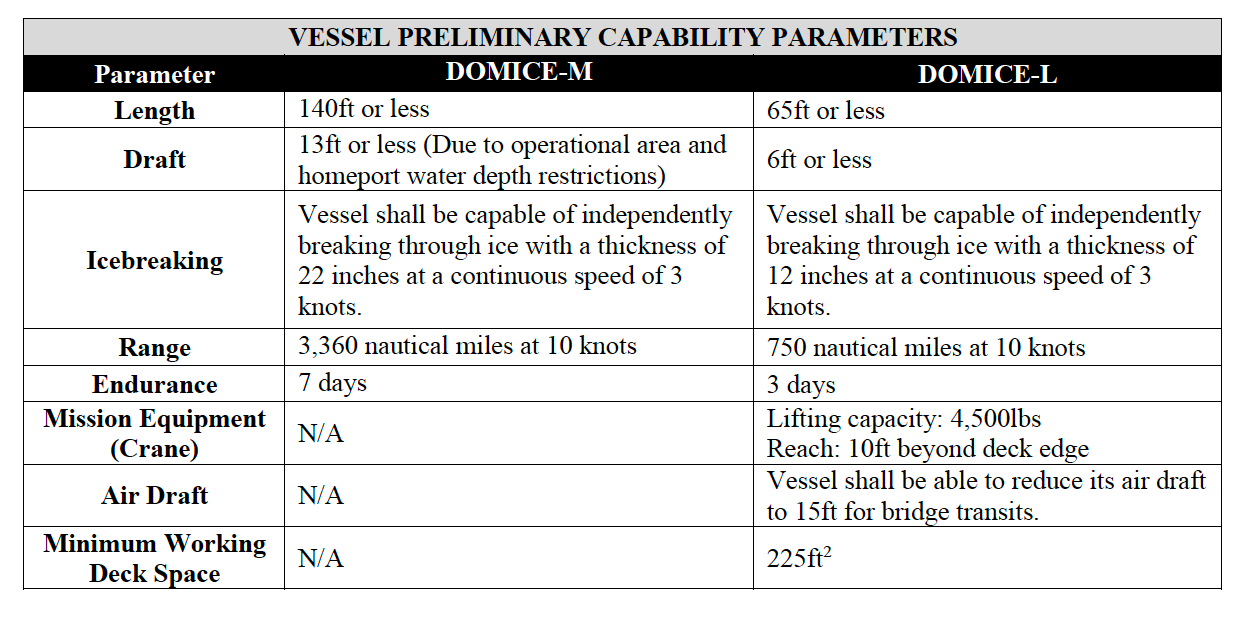

Crane and Deck Space

The MPI has a crane and working deck space for working with aids to navigation. This is not a mission of the ASC, but rather for U.S. domestic icebreakers. You can see the requirement for the crane and deck space in this chart from the U.S. Coast Guard’s Domestic Icebreaker RFI:

Thoughts and Comments:

The Multi-Purpose Icebreaker (MPI) is a great design that will significantly increase the capability of the CCG. In fact, this new class of buoy tenders meets the key requirements outlined in the U.S. Coast Guard’s own ASC RFI. But let’s be careful to not conflate the RFI into an exhaustive list of requirements for the ASC. As the RFI itself says:

Request for Information - Arctic Security Cutter (ASC): Icebreaking Capable Vessels or Vessel Designs that are Ready for Construction

The purpose of this RFI is to increase the USCG’s understanding of the current status and capability of both the U.S. and broader international maritime industrial base as it pertains to existing icebreaking capable vessels or vessel designs that are ready for construction or already in production.

Specifically, the USCG seeks to understand what existing vessels or production ready vessel designs satisfy or closely satisfy the below preliminary capability parameters. Additionally, the USCG would like to gain insight on recently proven execution and build strategies as well as the current capability and availability of global shipyards that could support the construction and subsequent launch of an existing icebreaking capable vessel design within THIRTY-SIX (36) months of a contract award date.

It is certainly possible to modify the MPI design to add propulsion power, increase crew size, install more electrical generation power, add weapons and sensors (or at least reserve power, space, and weight for them), increase survivability, and remove the crane.

However, the MPI is thoughtfully and specifically designed to meet all of the CCG’s requirements in a compact hull with a reduced carbon footprint. Redesign to address the concerns I listed above adds risk and time to the project10. One of the keys pushed by the consortium is that the MPI design is ready to build now.

The MPI is what it is—a solid design tailored to increase the capability of the Canadian Coast Guard within its design constraints. These constraints do not match those required by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Note that the MPI is not the CCG’s primary planned ship class for Arctic missions. Those would be the Polar Icebreakers and Program Icebreakers, as I wrote about above. However, the Polar Icebreakers are too large for the ASC, and we will likely not know enough about the Program Icebreaker design in time for the comparison to be relevant.

In short, the MPI is a great ship for what it is. But it is not an Arctic Security Cutter—at least not without substantial modification.

Thanks for reading. I hope that you found this article informative and interesting.

All the Best,

PGR

CCG vessels do, on occasion, embark members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and become temporary law enforcement vessels. The U.S. Navy does a similar thing, at times embarking a U.S. Coast Guard Law Enforcement Detachment (LEDET) to conduct law enforcement actions (such as drug interdiction).

To avoid having a ‘what is an icebreaker’ discussion today, I’ll use the numbers from Aker Arctic’s World Icebreaker Overview from last year. Note that this does not include only polar icebreakers, so it counts the U.S. as having sixteen icebreakers in service. (Polar icebreakers Polar Star, Healy, and the recently acquired Storis plus the nine Bay-class icebreaking tugboats, Great Lakes icebreaker Mackinaw, and three vessels operated in support of the National Science Foundation (Nathanial B. Palmer, Laurence M. Gould, and Sikuliaq.) Note that the Gould is now inactive, and Palmer’s contract was not renewed).

Note that there are also differing opinions on PC equivalence.

During a major overhaul (1998-1993), the ship was converted to diesel generators (from steam boilers) and her bow was replaced.

These vessels were all Icebreaking Anchor Handling Tug/Supply (AHTS) ships. Davie also considered, but rejected, purchasing and re-fitting the Aiviq which is now owned by the U.S. Coast Guard and in service as Storis.

Yes, the official NSS web page actually says ‘Coast Guard Canada.’

The vessels being replaced by the MPIs include two non-icebreakers, the High Endurance Multi-Tasked Vessel Sir Wildred Grenfell and the already decommissioned Medium Endurance Multi-Tasked Vessel Bartlett.

I’ve heard- but have been unable to confirm- that the MPI was designed to “Special Purpose Ship” standards, which are somewhat between cargo and passenger ship requirements.

A Seaspan executive is cited in a Defense News article from March as saying that the MPV “could be relatively easily upgraded to [polar] class 3.” It isn’t clear exactly how easy it would be to modify the design and maintain the 36 month timeline listed in the ASC RFI.

As an Air Force vet my opinion is not very well qualified, but that Harry DeWolf is a nice looking vessel

Enjoaybale and informative as always. Appreciate the post for a lunch time read as always!