Charcot's Summer: Operation Tugaalik, the Northwest Passage, and the Transpolar Sea Route

A quick look at what NATO's most capable icebreaker is up to this summer.

Back in May during a Congressional Hearing, witnesses were unable to describe a successful icebreaker program in response to a question. To help, I wrote an article about a very successful recent icebreaker program- Le Commandant Charcot. If you are unfamiliar with Charcot, she is a French-flagged Polar Class 2 icebreaker operated as a cruise ship by the French company Ponant.

Design for Charcot began in early 2016, and less than six years later- on September 9, 2021- Charcot was breaking ice at the North Pole. For more information on the construction and capabilities of this state-of-the-art modern icebreaker, please see my article from May:

In the article, I mentioned that Charcot had worked to break ice for government vessels including the UK’s RRS Sir David Attenborough and the Norwegian Polar Research Vessel Kronprins Haakon.

Charcot was recently in the ice again working with government vessels. This time her partners were the Icelandic Coast Guard, Danish Navy, and French Navy in Operation Tugaalik 2024.

Operation Tugaalik 2024

Operation Tugaalik 2024 was a Rescue and Assistance Exercise centered around Le Commandant Charcot involving Denmark, France and Iceland that took place in Arctic waters.

HDMS Triton

The exercise began on June 14th when Le Commandant Charcot and the Danish frigate HDMS Triton met off of Eastern Greenland, near Ittoqqortoormiit.

Here is how a NATO article describes HDMS Triton:

Since its launch in 1990, the ship has been a near constant presence in the waters around Greenland and the Faroe Islands, which are both autonomous territories within the Kingdom of Denmark and are therefore part of NATO territory.

The Triton serves a vital role in the defense of this highly contested and strategically important area, known as the High North, conducting patrols and returning to harbour in Denmark only for maintenance and to resupply. While not technically an icebreaker, the ship has been specially designed with a double skinned, ice-reinforced hull so that it can break through up to 80 cm of ice.

The exercise was not complex- Charcot simulated an onboard fire with injuries, and sailors from Triton provided assistance and evacuation via helicopter.

Notably, Triton required assistance from Charcot in the ice. First, Charcot escorted Triton through the ice until the vessels reached a relatively ice-free area known as a polynya (sometimes called an ice-free lake) where the Rescue and Assistance (R&A) exercise took place. Following the exercise, Triton became stuck in thick pack ice as she approached Ittoqqortoormiit. Fortunately, Charcot was able to free Triton. Here is how Captain Patrick Marchesseau described the maneuver:

It’s a tricky maneuver, because you have to get close enough to the ship to open up a channel, without compressing it or squeezing it further by pushing chunks of ice towards it as you pass, or even colliding with the vessel. You need to have perfect control over the power and maneuverability of your vessel. For this operation, we used 50% of the ship’s maximum power.

BSAM Rhône

Rhône is another vessel with an Arctic history. From August to September 2018, before being accepted into the French Navy, the vessel- now designed a BSAM, or Metropolitan Offshore Support & Assistance Vessel- sailed through the Northeast Passage from the Norwegian Sea to the Bering Strait. It was this passage that prompted Russia to change its rules for sovereign foreign vessels operating in the Northern Sea Route.

Rhône and Charcot conducted their exercise on June 23rd. According to Cmdr. Krystyn Pecora of the U.S. Coast Guard, who observed the exercise:

The Rhône trailed Charcot into the icefield from approximately 500-1000 yards behind the vessel. The width and ice breaking capabilities of Charcot made an ample channel for Rhône to safely transit within. Both vessels traveled within the icefield until a “lake” was reached, at which time both vessels maintained a separation distance. The Charcot simulated two personnel casualties, and the Rhone sent a medical team via small boat to respond to the casualties. The Charcot displayed impressive maneuverability within the lake. Small boats easily maneuvered within the “lake” for the medical exercise and passenger transfer purposes.

Following lunch, the Rhône followed the Charcot out of the ice field back to open waters (seas 1-2 feet). Rhône conducted a pre-tow brief with the Charcot in French and then conducted the approach by crossing the T.

Icelandic Coast Guard Vessel Thor

Thor and Charcot conducted a TOWEX on June 24th. According to Cmdr. Pecora:

The Charcot rendezvoused with the Icelandic Coast Guard vessel Thor for another towex. For both towing exercises, civilian passengers were allowed on the bridge to view the exercises from the bridge. All communications between Thor and Charcot were conducted in English, seas were 2-4 feet. Thor used a parallel approach for its initial approach; however, the messenger parted requiring a second approach facilitated by Thor backing down for a second shot. Tow length was approximately 300 M and achieved a speed of 8 knots. Due to Charcot’s unique bottom, the tow was significantly offset to Thor’s port, which according to Charcot was a common occurrence during these exercises.

Some of Cmdr. Pecora’s thoughts on Le Commandant Charcot:

Bridge Layout and Control Stations:

Charcot had three separate conning control stations and was nearly all automated; the view aft was limited due to the super structure of the vessel but aided by live camera feeds when necessary. These live camera feeds also included spaces aboard the vessel, which was vital during the towing exercises as the deck space for line handling was below the flight deck on the bow and not visible to the bridge.

There were numerous computerized displays and controls throughout the bridge to manage and monitor engineering equipment, weather, and navigational controls. Charcot also had satellite imagery of the icefield being directly fed to one of the displays on the bridge to aid navigation. The refresh rate of this imagery was impressive as Charcot and Rhône’s route into the ice was visible within two hours of its occurrence. Additional features included a sizeable touch screen “chart table” that enabled a much easier manipulation of electronic charts than traditional mouse-controlled technology.

Accommodations and MealsPassenger accommodations were superb with nearly every stateroom having a balcony. Crew berthing was for one to two individuals per room. There were multiple meal options including room service, buffet style dining and an Alain Ducasse restaurant. Three meals and a tea/snack course were served throughout the day; food quality was exceptional. Internet aboard was facilitated by Starlink; however, there were periods where coverage seemed to be impacted by the vessel’s location.

Special thanks to Cmdr. Krystyn Pecora of the U.S. Coast Guard for providing her observations from Operation Tugaalik.

Thoughts on the Exercise

Cruise ships frequently participate in Rescue and Assistance exercises. What makes this one different is that it was the cruise ship itself- Le Commandant Charcot- that permitted the exercise to take place in icy Arctic waters.

Not only did Charcot escort vessels into icy waters, but she broke a free Danish frigate specifically designed to patrol the icy waters of Greenland.

Next: Northwest Passage and Transpolar Sea Route

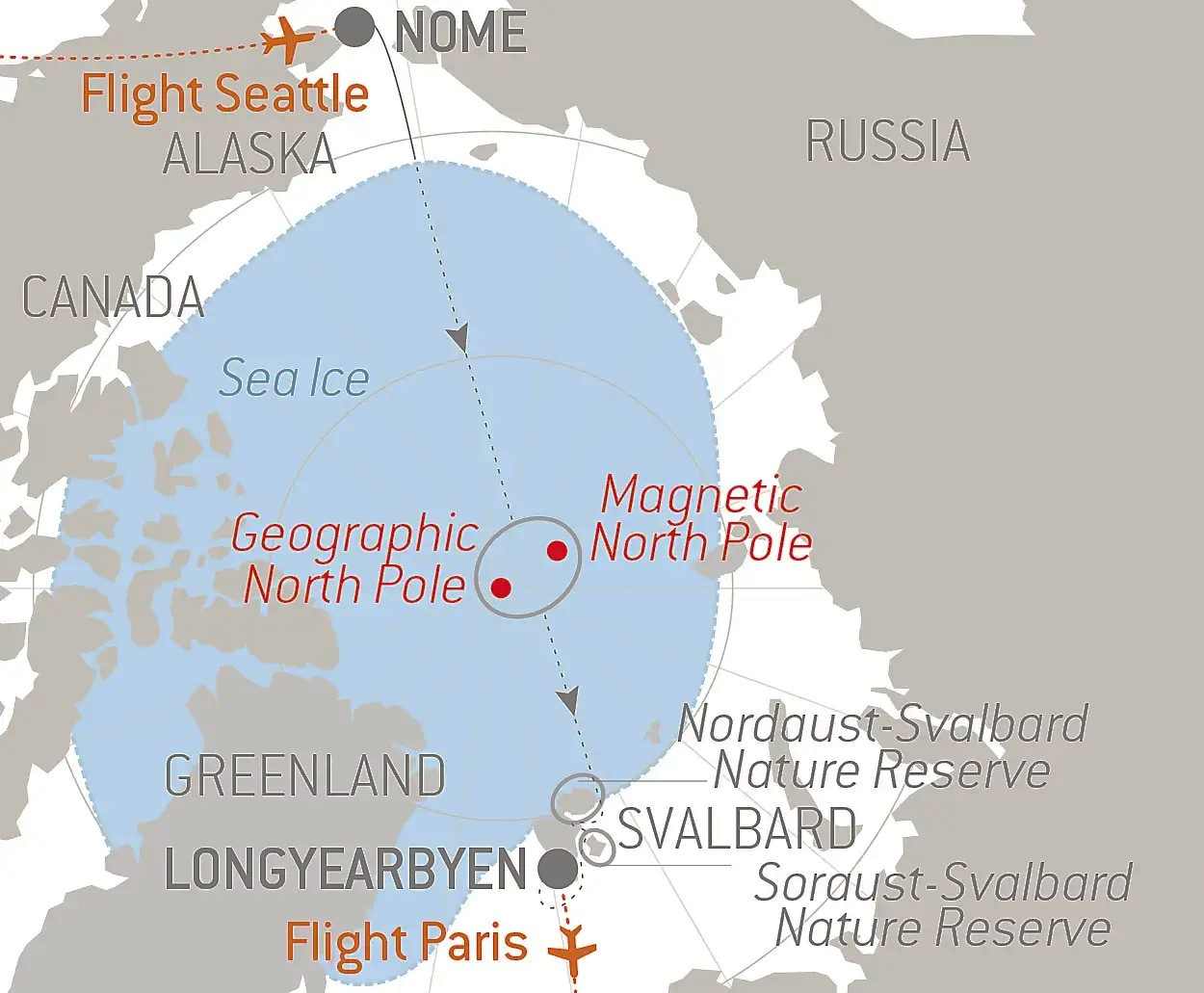

As I write this, Charcot is on her way to Nome, Alaska through the Northwest Passage, scheduled to arrive on September 5th:

Following that cruise, Charcot will return to European waters via the Transpolar Sea Route (September 6-26th):

This Transpolar Sea Route cruise is a BIG DEAL.

There have been quite a few partial transits and North Pole visits1, many heading through the shorter ice field from Iceland to the North Pole. However, very few ships have sailed the Transpolar Sea Route. The 2009 Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (2009) lists seven trans-Arctic voyages across the central Arctic Ocean through the North Pole:

1991: Russian Nuclear Icebreaker Sovetskiy Soyuz- Tourists

1994: Louis S. St-Laurent (Canada) and Polar Sea (USA)- Scientific Research

1996 (twice): Russian Nuclear Icebreaker Yamal- Tourists

2005: Oden (Sweden) and Healy (USA)- Scientific Research

I’ve been able to find out about a few more by asking former icebreaker Captains and others interested in Polar Navigation. (Special thanks to Captain Anthony Potts and Duke Snider):

2010: Russian Nuclear Icebreaker Rossiya- Rescue of Ice Station NP-37 crew

2014-2015: Louis S. St-Laurent (Canada) and Terry Fox (Canada): Scientific Research

2015-2016: Lous S. St-Laurent (Canada) and Oden (Sweden): Scientific Research. (Note: Oden did not complete a full transit)

Note that all of the non-nuclear vessel transits were in pairs.

As the Transpolar Sea Route is not specifically defined, my list is probably missing some. There is also at least one transit advertised as Transpolar that apparently does not belong in that category:

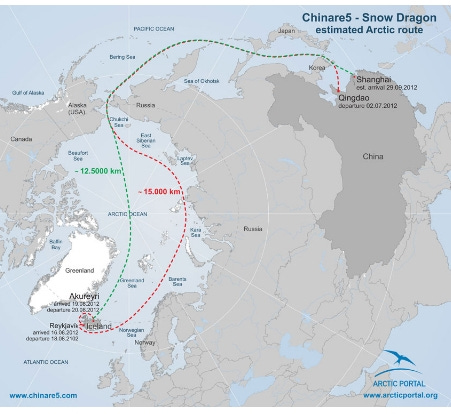

Wikipedia reports that China’s Xue Long used the Transpolar Sea Route in 2012. Although apparently planned, a look at Xue Long’s actual route (in the middle of this page, as opposed to the planned route in the upper right) shows that she did not make it:

On the way towards the North Pole, the ice conditions became more severe, with increased proportion of thicker multi-year ice.

On August 30th, Xue Long reached its farthest point north on this cruise, at 87°39'N, 123°11'E. On the way south again, the ship went through patches of new ice formation.

Charcot will be the first commercial vessel to use the Transpolar Sea Route, and also apparently the only non-nuclear vessel to do it alone. And she plans to go again next year, and probably the year after. After all, this year’s cruise was sold out (despite the cost).

Concluding Thoughts

There are some who dismiss the capabilities of Charcot, suggesting that although she can break ice, she does not meet the survivability and stability requirements of a U.S. Coast Guard vessel. Ponant obviously views Charcot as safe, stable, and survivable; otherwise, it would not send Charcot through these waters with paying passengers (next year’s Transpolar Sea Route Cruise starts at about 40k Euro per person, double occupancy).

With that in mind, I’m blowing the dust off of an article I started several months ago that compares MILSPEC/MIL STD to the current commercial requirements for icebreakers- the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code, which entered into effect in 2014, and the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) Polar Class standards, which entered into force in 2007. Fortunately, people with more experience in this area have closely analyzed these specifications, and I will be looking at their conclusions.

Thanks for reading. If you like what you’ve seen, press the heart and subscribe to make sure that you never miss an update. With so much recent news concerning icebreakers, subscribing is the best way to ensure that you stay current on the news and its wider implications. Consider sharing with a friend, work colleague, or family member; it takes me some time to research and write these articles, so I’m happy to see them spread far and wide. It’s important to keep this conversation going.

Until next time.

All the Best,

PGR

According to this website there were 154 North Pole visits through 2021, 122 of which were done by nuclear-powered Russian icebreakers. The non-Russian vessels that have visited the North Pole are Oden (9), Polarstern (6), Louis S. St-Laurent (3), Polar Sea, Healy (3), Vidar Viking (1), Terry Fox (1), Svalbard (1), and Le Commandant Charcot (1). Numbers indicate visits through 2021. Several of these vessels, including Healy and Charcot, have made additional visits since the list was compiled. Additional ships, including Norway’s Kronprins Haakon and China’s Xue Long 2, have also reached the North Pole since 2021.

See if some company will pay for you to go next year!