The Last Days of Corporal Matyola, Part 3: Killed in Action.

Part 3 of a series on my Great Uncle's World War II Service

Eighty years ago today— November 19, 1944 —25-year-old Private Peter ‘Pinto’ Matyola was killed by enemy artillery fire near the town of Siersdorf, Germany- nearly 4,000 miles away from the New Jersey town he called home.

On May 27, 1945, my father was born. His mother- Peter’s sister, Anna- named him Peter in honor of her brother. I carry on the name as well.

At the end of the previous installment (Part 2) about his service, Pinto had just arrived in Europe as a designated replacement soldier.

On October 12th, 1944, Pinto reported to Company K of the 115th Infantry Regiment, a part of the 29th Infantry Division.

The 29th Infantry Division- “The Blue and the Gray”

(Note: The 29th Infantry Division almost lost its patch and special designation as “the Blue and the Gray.” However, in 2022 the naming commission (the same one that changed Fort Bragg to Fort Liberty) reversed itself and recommended keeping the patch and designation.)

The 29th Division, originally organized for the First World War, was called back into active service in early 1941 (prior to Pearl Harbor). Following reorganization and training, the unit shipped out for England in September 1942 and spent almost two years training together prior to the invasion of Normandy. The ‘Stonewallers1’ of the 29th Division’s 116th Infantry Regiment came ashore during the first wave of the bloody assault on Omaha Beach.

From June through October, the 29th Division fought at Normandy, Saint-Lô, and Brest, suffering in excess of 15,000 casualties, including 3,000 dead along the way. This total was more than 100% of its nominal 14,000-man strength.

The 29th was then shipped east to the Dutch-German border region. It was in this area that the 29th Division had what historian Joseph Balkoski called its “most devastating defeat of World War II.” (From Brittany to the Reich, 111)

On October 4th, K/115 ceased to exist as a unit following a disastrous assault against the town of Schierwaldenrath. In order to reconstitute the unit, 125 replacements- including Pinto- would be assigned to this ‘newly formed’ K/115. In the wake of this disaster, K/115 would have the lowest morale, as evidenced by AWOL and other offenses, of any 29th Division unit during the war.

K/115 and Schierwaldenrath

The Commanding General of the 29th Infantry Division, Major General Charles H. Gerhardt, ordered K/115 to seize the town of Schierwaldenrath. With only eighty-five men available and no reinforcements, the Commanding Officer of Company K, Captain Waldo Schmitt, did his best. With the eighty-five men he had available, his company was able to take the southern fringe of the town before nightfall. But the Germans were able to bring in reinforcements overnight and counterattack in strength the following morning. With no Battalion or Regimental reserves available to reinforce Company K, the counterattack all but destroyed the unit. After the assault, Company K could muster only 19 men- and most of those were company staff or members of the mortar section who had not taken part in the assault. Captain Schmitt himself was wounded and captured. He would die in captivity.

Instead of questioning the wisdom of an unnecessary assault against an enemy of unknown strength without reserves, General Gerhart publicly blamed Captain Schmitt for the loss, as he had violated one of Gerhardt’s rules, setting up his HQ inside a building:

Over the next few weeks, many members of the 115th seethed when they observed Gerhardt’s unforgiving attitude towards Schmitt displayed in briefings in which the general derisively urged 29ers “not to do a ‘Schmitt’ and get caught by the enemy inside buildings.” (From Brittany to the Reich, 109-110)

Joseph Balkoski2 sums it up well:

Only one man had ordered the attack, and that was Gerhardt. With limited manpower and no backup, that order specified that Schmitt was to seize an ememy-occupied town, knowing nothing about its defenses or the size of its garrison. Furthermore, he was forced to hold on with no support against an overwhelming enemy counterattack. The disaster had more to do with an astonishing imprudence, triggered by gross overconfidence and faulty intelligence, than it did with alleged violations of 29th Division rules by a mere company commander. Gerhardt’s intractable attitude sealed Company K’s fate the moment it launched the attack. (From Brittany to the Reich, 111)

Rebuilding K/115

Over the next few days, the 115th rebuilt the unit almost from scratch: Companies I and L each transferred twenty men, and the 86th Replacement Battalion sent over 125 more, among them five new officers…. (Our Tortured Souls, 64)

Among this group was undoubtedly Pinto. Being a replacement soldier was hard enough, according to many contemporary reports from the European Theater of Operations (ETO). Things were particularly challenging, though, in the rebuilt Company K. Balkoski continues:

The challenge of converting such a throng into a battleworthy rifle company, however, was difficult, and within the 3rd Battalion nagging doubts about Company K’s competence worsened as consistent morning report entries of men either under arrest or AWOL suggested a serious morale problem. Ordinarily such offenses were rare within the 29th Division; that something was indeed wrong, however, became clear on the last day of October when a senior NCO committed a sin Gerhardt could not forgive. The acronym SIW next to the transgressor’s name on a Company K morning report told a startling story: self-inflicted wound. (Our Tortured Souls, 65)

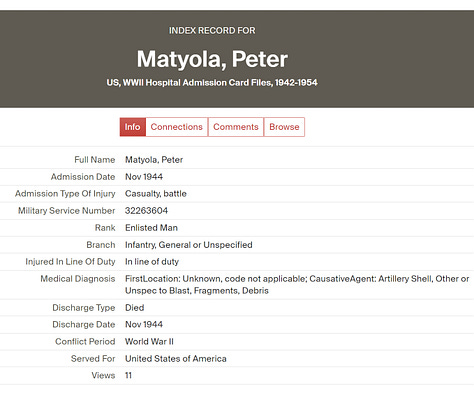

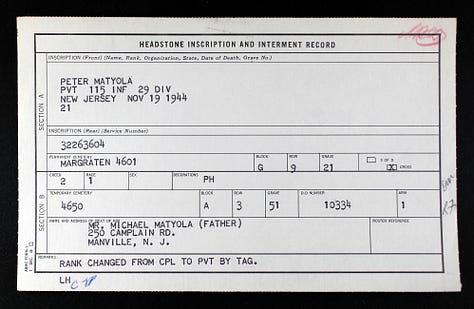

If you’ve been reading along, you’ll note that I had been referring to Corporal Matyola- yet his headstone shows his rank as Private. All I can do is speculate that it was the low morale of K/115, possibly combined with notice of his mother’s death, that led to his reduction in rank and confinement for AWOL, as noted in this summary of actions related to Peter Matyola from the company’s daily reports:

Note: It seems odd to me that he was busted straight to Private from Corporal, and not to Private First Class, and that this occurred before he went AWOL. Maybe someday I will be able to learn more about what transpired, perhaps after a research visit to the 29th Division archives.

Assault on Siersdorf

Pinto returned to duty on 16 November in time to take part in Operation Queen, in which the 29th Division would advance through the Rur plain. With wide open farmland between small, fortified towns the 29th Division found the assault tough going. Siersdorf features two prominent buildings, the Kommende and St. Johannes Church. Some of the heaviest fighting occurred near these buildings.

Based on some accounts I’ve read, K/115’s line of assault was the road shown in the first photo. I took this picture from Siersdorf, looking back towards Baesweiler. The only two tall buildings in the area- the Chruch and Kommande also pictured above- were near be as I took the first photo.

I took these pictures to during a visit to Siersdorf earlier this year. I couldn’t imagine an assault across this flat ground against an entrenched enemy with ample pre-spotted artillery, with artillery spotters located in the Church and the Kommande building.

It was in this assault on Siersdorf that Pinto was killed by artillery fire on November 19th.

For a sense of what life was like for the ordinary soldier, I suggest the book Heaven, Hell, or Home:

The author, Edwin McIntosh, was part of A/115. Although not a true memoir or work of history, the book conveys the feeling of combat from the perspective of a junior draftee serving with a regular infantry unit. This isn’t Band of Brothers. The story begins with a bunch of replacements reporting to the 115th in Siersdorf, seemingly the day after Pinto was killed. I highly recommend this book for its perspective, as it is not one that we normally get in movies and books.

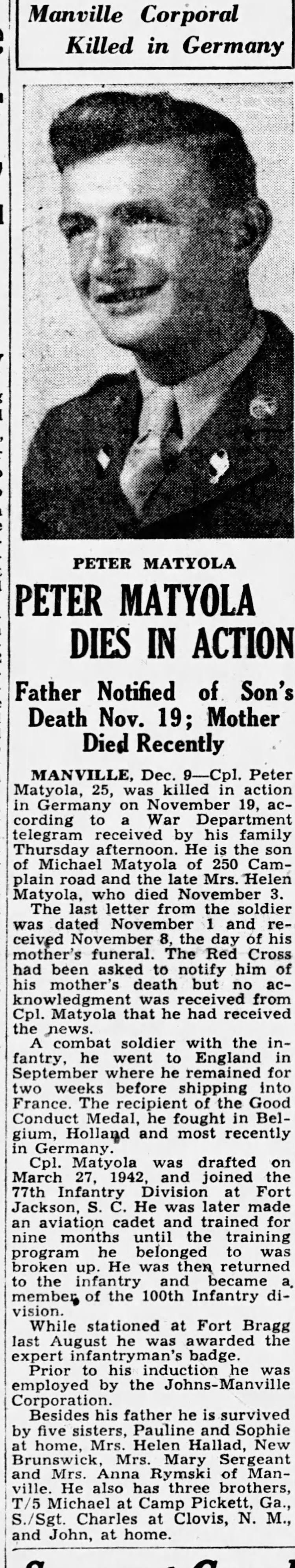

The following obituary ran in the local newspaper in early December. It contains at least one error (Pinto is still listed as a Corporal) and a few things I could not verify (combat in Belgium and Holland).

Rest In Peace, Pinto. We have the watch.

Sources of Information:

Some of you are probably trying to research your own family history. For many soldiers, this is challenging because 16-18 million Official Military Personnel Files were destroyed in a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records center. Peter’s file was among those destroyed. However, with the digitization of many records (and many still to come) there are some good sources of information out there/

Here are some places where I found information for this post:

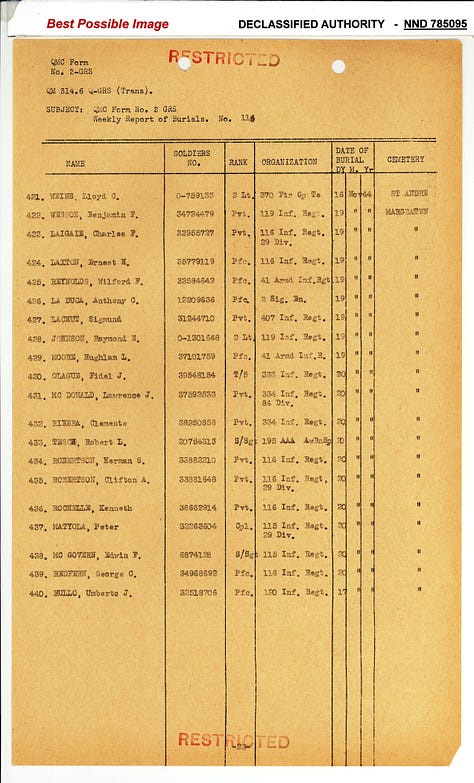

The National Archives: You can search the online archives by name and date and find some records. This is how I found the Burial Report and Interment Record, as well as some of the information I used in earlier posts (registration cards, induction information, etc).

Ancestry.com: Provides some searchable databases. Its partners Fold3 and Newspapers.com are also searchable by name.

Company daily reports: Sources can vary. The 29th Division Association has an excel spreadsheet of all daily reports available to its members.

The 116th Infantry Regiment traces is history back to the Bull Run, where it was the senior regiment in the famed Stonewall Brigade of General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson.

Joseph Balkoski is the author of a five-volume history of the 29th Infantry Division in the Second World War. I cite passages from two of his books, From Brittany to the Reich: The 29th Division in Germany, September 1944-November 1944 and Our Tortured Souls: The 29th Infantry Division in the Rhineland, November-December 1944. I highly recommend this series.

What a wonderful way to honor your great uncle, to make a contribution to your family’s collective memory, and to document the harsh and unforgiving reality of infantry combat. The fact that he was awarded the EIB is impressive. When I was documenting my Dad’s service (WWII Pacific) I found his records at the National Military Personnel Records Center had been destroyed (along with 16-18 million others) in the July 1973 fire. Thankfully he had saved his discharge papers and other records with the details of his service, so we were able to submit those to the Center and get a notarized certificate documenting his service (but without any details thereof). He fought at Okinawa, and I was fortunate enough to be stationed there in the 90’s. I had heard his stories and studied the battle since childhood, so I was able to help Armed Forces TV make an hour-long documentary about the battle and participate in interviews with U.S. veterans and Okinawans. I served as a battlefield guide for veterans that visited the island, and accompanied Japanese congregations on the somber task of searching for remains of the missing. I met my wife there — she was working for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as an architect (she’s Japanese-Filipino-American, her Mom and Dad were both survivors of the war). Turns out our birthday’s are identical — day, month, year. Felt like kismet to us! My son, a Green Beret, was later stationed there. We took the whole family to the island of Ie Jima, about 5 miles off the coast of Okinawa (where my Dad had participated in fierce fighting in April 1945) and were able to recreate a three-generation photograph of one my Dad had of he and a buddy next to the just-constructed 77th Infantry Division memorial to Ernie Pyle, the famous war correspondent. (my Dad was mine-detecting about 100Y away when Pyle was shot). Who could have imagined that 19 year old would beget a family so thoroughly intertwined with his wartime experience? I don’t know if the appropriate word is closure or continuity. Probably both.

Wow. That's wild.