How Many Icebreakers Does the U.S. Coast Guard Need? Reviewing the Requirements.

The answer isn't two or forty. Eight to ten seems right.

Note: This series considers polar icebreakers, not harbor or other icebreakers such as those used on the Great Lakes.

If you’re new to the channel, it might be helpful to look at my earlier piece about polar icebreakers:

A Quick Note about Icebreakers

Russia has forty. The U.S. has two.

You have all probably seen news stories during the past several years highlighting the gap between the number of polar icebreakers operated by the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG)- two - and the number operated by Russia- usually listed as forty. Some articles are intended to be a call for action to catch up, others minimize the importance of the large difference. Russia, which has a long Arctic coastline and depends on maritime shipping along it, obviously has different requirements for icebreaking than the USA. Therefore, a simple comparison of numbers doesn’t shed much light on how many icebreakers the USCG actually needs to accomplish its missions, and what that fleet would look like.

We need eight or nine. But why?

During 2023 Congressional Testimony, multiple officials from the USCG stated that they require eight or nine polar icebreakers, including four to five “heavy” icebreakers, in order to meet the polar mission requirements established by the U.S. Government1. Although the USCG did not release this most recent analysis, a look at public information released over the past ten years or so can help inform the number.

We’ll start by looking at the USCG’s assigned roles and missions related to the polar regions. Then we will take a look at a 2011 Department of Homeland Security Inspector General report that assesses how well the USCG is completing these assigned missions. Then we will consider the 2010 High Latitude Report analysis of how many polar icebreakers it would take to actually meet the mission requirements2.

U.S. Coast Guard Polar Missions

14 U.S. Code 102 lays out the USCG’s seven primary missions, two of which specifically mention icebreaking:

The Coast Guard shall—

(4) develop, establish, maintain, and operate, with due regard to the requirements of national defense, aids to maritime navigation, icebreaking facilities, and rescue facilities for the promotion of safety on, under, and over the high seas and waters subject to the jurisdiction of the United States;

(5) pursuant to international agreements, develop, establish, maintain, and operate icebreaking facilities on, under, and over waters other than the high seas and waters subject to the jurisdiction of the United States;

And here are the missions of the USCG according to The Homeland Security Act of 2002:

(1) NON-HOMELAND SECURITY MISSIONS.—The term ‘‘non homeland security missions’’ means the following missions of the Coast Guard:

(A) Marine safety.

(B) Search and rescue.

(C) Aids to navigation.

(D) Living marine resources (fisheries law enforcement).

(E) Marine environmental protection.

(F) Ice operations.(2) HOMELAND SECURITY MISSIONS.—The term ‘‘homeland security missions’’ means the following missions of the Coast Guard:

(A) Ports, waterways and coastal security.

(B) Drug interdiction.

(C) Migrant interdiction.

(D) Defense readiness.

(E) Other law enforcement.

According to Ron O’Rourke of the Congressional Research Service, U.S. polar ice operations are currently needed to support all of these missions except fisheries law enforcement and migrant interdiction. He then summarizes the roles of the USCG’s icebreakers based on these (and other) requirements:

Conducting and supporting scientific research in the Arctic and Antarctic;

Defending U.S. sovereignty in the Arctic by helping to maintain a U.S. presence in U.S. territorial waters in the region;

defending other U.S. interests in polar regions, including economic interests in waters that are within the U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ) north of Alaska;

monitoring sea traffic in the Arctic, including ships bound for the United States; and

conducting other typical Coast Guard missions (such as search and rescue, law enforcement, and protection of marine resources) in Arctic waters, including U.S. territorial waters north of Alaska3.

The first bullet- conducting and supporting scientific research- might seem to not directly support the missions outlined in 14 USC and the Homeland Security Act. There are however a series of statutes, presidential directives, national security directives, and interagency agreements which firmly place and prioritize Arctic and Antarctic scientific research support for the USCG’s icebreakers. In fact, from 2005 until 2011, Budget Authority for the USCG Polar Icebreakers was placed primarily with the National Science Foundation. Only after a scathing IG report was that authority returned to the USCG.

Polar Mission Accomplishment Grade: F

From a January 2011 report from the Department of Homeland Security’s Inspector General4:

The Coast Guard is unable to accomplish its Arctic missions with the current icebreaker resources.

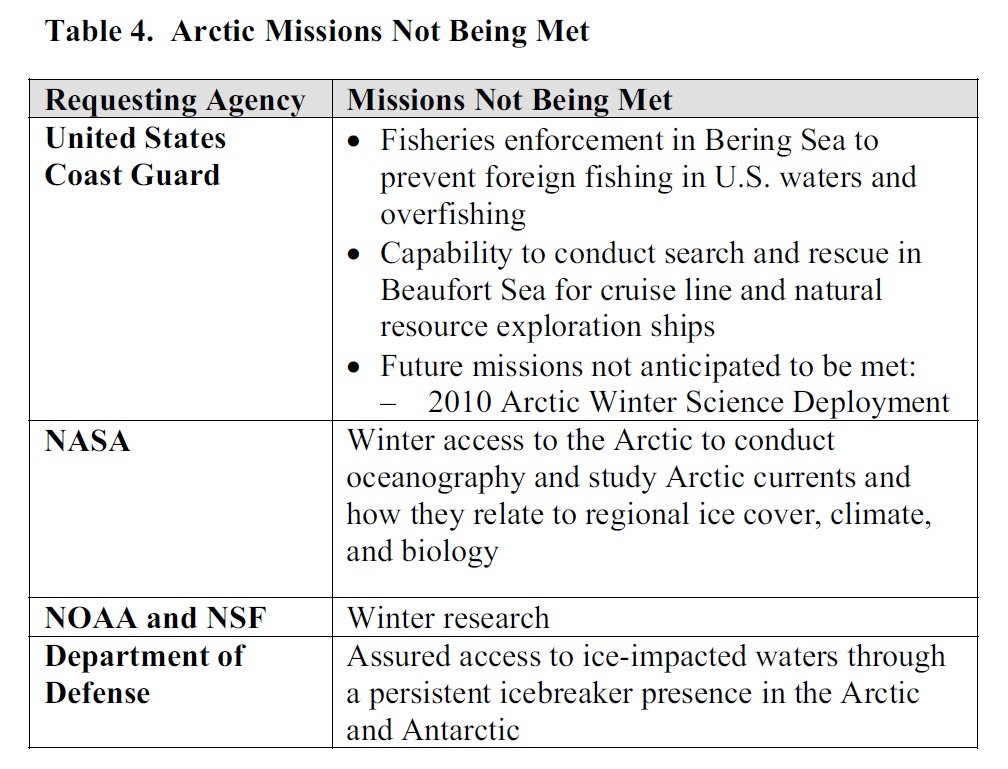

The Coast Guard’s icebreaking resources are unlikely to meet future demands. Table 4 outlines the missions that Coast Guard is unable to meet in the Arctic with its current icebreaking resources.

And on the Antarctic side:

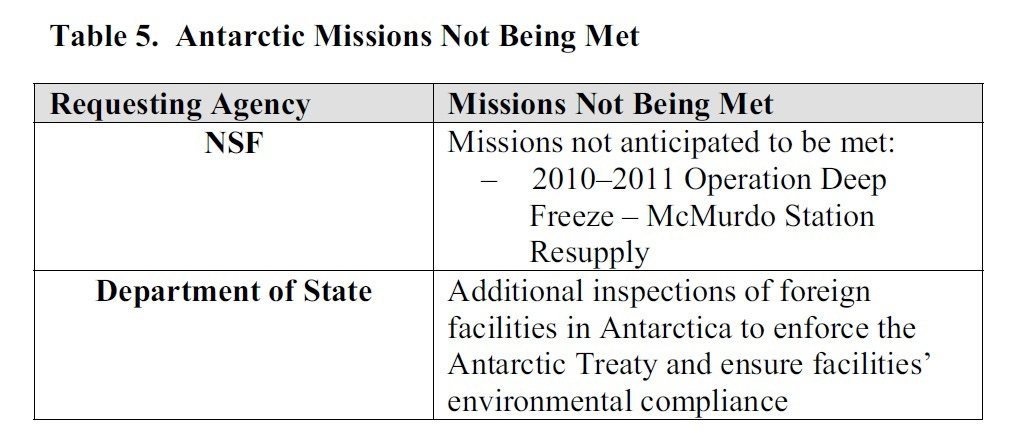

The Coast Guard Is Unable to Accomplish Its Antarctic Missions With Current Icebreakers

The Coast Guard needs additional icebreakers to accomplish its missions in the Antarctic. The Coast Guard has performed the McMurdo Station resupply in Antarctica for decades, but with increasing difficulty in recent years. The Coast Guard’s two heavy-duty icebreakers are at the end of their service lives, and have become less reliable and increasingly costly to keep in service.

Table 5 outlines the missions that will not be met without operational heavy-duty icebreakers.

When the DHS IG wrote this report, the USCG only had one operational icebreaker, the “medium duty” Healy. The Polar Sea had suffered a catastrophic engine failure, and the Polat Star had been in an ‘inactive’ status since 2006. By the end of 2012, the Polar Star had returned to normal service and the USCG was back to where it had been and is now- with two operational polar icebreakers, Polar Star and the Healy. Polar Sea currently serves as a parts depot for Polar Star. The National Science Foundation could once again re-supply McMurdo station without having to charter a foreign icebreaker5.

But aside from that one change, the situation remains the same. The USCG is not accomplishing its required missions.

What It Would Take to Accomplish Assigned Missions

The 2010 High Latitude Region Mission Analysis6 directly considered how the USCG could accomplish all of its polar missions. Through mission analysis and Operations Research tools, it considered how to optimally design and employ a fleet of polar icebreakers to accomplish the USCG’s polar missions. Here is how the fleet would be employed:

Arctic North Patrol. Continuous multi-mission icebreaker presence in the Arctic.

Arctic West Science. Spring and summer science support in the Arctic.

Antarctic, McMurdo Station resupply. Planned deployment for break-in, supply ship escort, and science support. This mission, conducted in the Antarctic summer, also requires standby icebreaker support for backup in the event the primary vessel cannot complete the mission.

Thule Air Base Resupply and Polar Region Freedom of Navigation Transits. Provide vessel escort operations in support of the Military Sealift Command’s Operation Pacer Goose; then complete any Freedom of Navigation exercises in the region.

Assured access and assertion of U.S. policy in the Polar Regions. The current demand for this mission requires continuous icebreaker presence in both Polar Regions.

“Operations to support National Science Foundation (NSF) research activities in both polar regions account for a significant portion of U.S. polar icebreaker operations.”7 This accounts for the McMurdo re-supply and the Healy’s annual Arctic West Science mission8. So how many icebreakers would it take to do it all? Back to the High Latitude Report:

The Coast Guard requires three heavy and three medium icebreakers to fulfill its statutory missions.

The Coast Guard requires six heavy and four medium icebreakers to fulfill its statutory missions and maintain the continuous presence requirements of the Naval Operations Concept.

Applying non-material alternatives for crewing and homeporting reduces the overall requirement to four heavy and two medium icebreakers9.

Missions at Risk with the U.S. Coast Guard’s Current Fleet

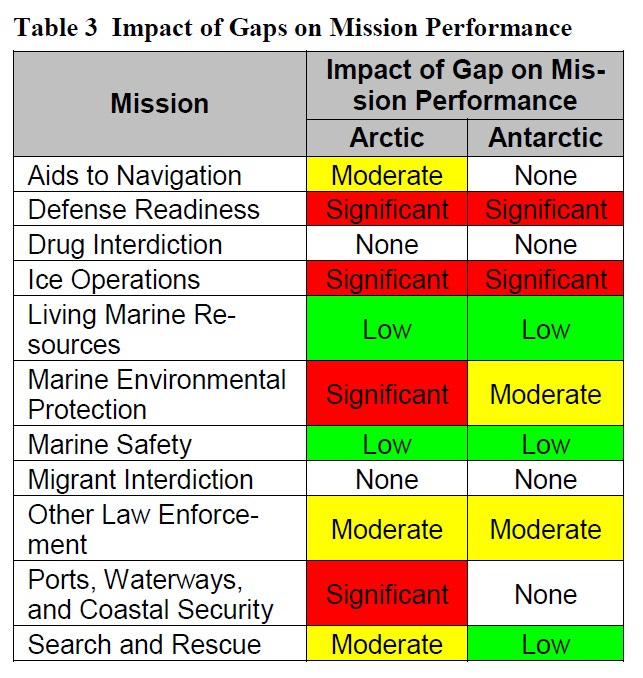

With the current gap between available and required resources, the report analyzed the risk to mission accomplishment:

Eight, nine, or ten?

This analysis dates back to 2010. There have been a few changes since then that may have been considered in the more recent (but unavailable) analyses. First, the USCG and Canadian Coast Guard adopted a Memorandum of Understanding in which the Canadian Coast Guard provides support for Operation Pace Goose, the mission that supplies Thule Air Force Base on Greenland. Second, in 2017 the Department of Defense told the GAO that an updated defense strategy no longer required year-round polar icebreaking support in the Arctic and Antarctic10.

It seems likely that the newer studies added requirements, as Arctic maritime activity and security concerns have increased throughout the past decade. In the October 2022 National Strategy for the Artic, persistent presence in the U.S. Arctic is back, along with additional presence “as needed” in the European Arctic11.

So, although we don’t know the actual breakdown in the new reports, it seems reasonable to start with the 2010 analysis, equate presence in the European Arctic with the Thule re-supply mission, and remove the continuous Antarctic presence requirement. By some back of the napkin Global Force Management calculations12, that yields a requirement of about eight or nine icebreakers (depending on the standby/backup requirements). The mix of capabilities (high/low or heavy/medium, as the USCG prefers) is a bit more challenging to fit on a napkin, but if you assume that high/heavy capability is needed for the McMurdo re-supply mission and for Arctic operations in winter, the “eight or nine” with “four or five heavies” makes sense.

Concluding Thoughts

The USCG has too few polar icebreakers to accomplish all of the U.S. Government’s requirements. The polar icebreakers that the USCG does have are old and use dated technology. The Polar Star is about 48 years into a 30-year service life, and the Healy will reach the end of her service life in 2029 (which I’m sure will be extended). Meanwhile, the program to build new icebreakers, called Polar Security Cutters, is delayed with delivery dates slipping into the next decade. The first vessel, when/if delivered, will replace the Polar Star, pushing actual growth in the polar fleet even further into the future. While we await these new vessels, Polar Star and Healy, both of which have had recent mechanical problems, remain single points of failure.

As a nation, we’ve been ignoring this mission set for so long; why should we prioritize it now? In short, Arctic conditions are changing, vessel technology is changing, and the world’s shipping routes are changing. Maritime activity in and around the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) has been rapidly growing through the past decade and has the potential for still much greater growth. Large deposits of natural resources, in and around our EEZ are becoming more accessible. With our competitors China and Russia cooperating in the Arctic, we must have the capability to monitor and, if necessary, respond to their actions. Additionally, the U.S. Coast Guard must be able to respond to vessels in distress and potential environmental disasters in and around these waters.

Stay tuned, we will look at these changes in some detail in the future.

If you would like more detailed analysis, the Congressional Research Service Report is a great place to start and has a great bibliography to other source documents.

Thanks for reading, subscribing, and spreading the word.

PGR

The U.S. Coast Guard is responsible for conducting all polar icebreaking operations, including those supporting other government agencies such as the Department of Defense and the National Science Foundation.

Although there are more recent reports and analyses, they have not been released publicly (at least I could not find them).

For a number of reasons, chartering of a foreign icebreaker is no longer feasible. Nordic nations require their vessels to be in or near home waters during Northern Hemisphere winters, and political considerations/sanctions preclude Russian vessels. There aren’t any others that can handle the mission.

United States Coast Guard High Latitude Region Mission Analysis Capstone Summary, July 2010.

CRS Report RL34391, Coast Guard Polar Security Cutter (Polar Icebreaker) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, pg 2. Updated January 17, 2024.

Polar Star’s McMurdo resupply mission was cancelled for 2020-2021 due to COVID concerns, allowing her to complete a rare winter Arctic mission instead. Healy normally supports an annual Arctic West deployment that is mainly in support of scientific research but, of course, provides presence and offers other Coast Guard functions.

Throw away Course of Action. The U.S. Coast Guard is short of personnel today, and the complex nature of setting up an overseas base would only delay the programs further. I never met a U.S. Coast Guard official who seriously thought that multiple crews or new, Southern Hemisphere bases would be a good idea.

Frankly, this is unbelievable and seems to have been walked back.

Generally, you need three ships to achieve continuous presence in a location- one on station, one preparing for the mission, one undergoing maintenance.