Life in Finland: Back to School Edition

A look at some of the things that surprised us about public education in Finland.

First, allow me to offer a warm welcome to those of you who have recently subscribed to Sixty Degrees North. There was a nice bump in subscriptions after Brian Potter referenced me in his excellent article on building ice-capable vessels over at Construction Physics. Note that Sixty Degrees North is not only about icebreakers; occasionally I do write on other topics. Today is one such (long-promised) day.

Finnish schools are different- but maybe not in the ways that you imagine.

Some of you may have heard or read about Finland’s excellent public school system. Every so often, there is an English-language article published or shared on social media about the Finnish education system. Those articles often either don’t match our1 experience here in the Finnish language public schools or leave out some key aspects of how things work. Today, we’ll be looking at some practical aspects of the Finnish system that differ from what we saw in the USA. Our main purpose isn’t to refute those articles although some of what we say probably will contrast with what they say..

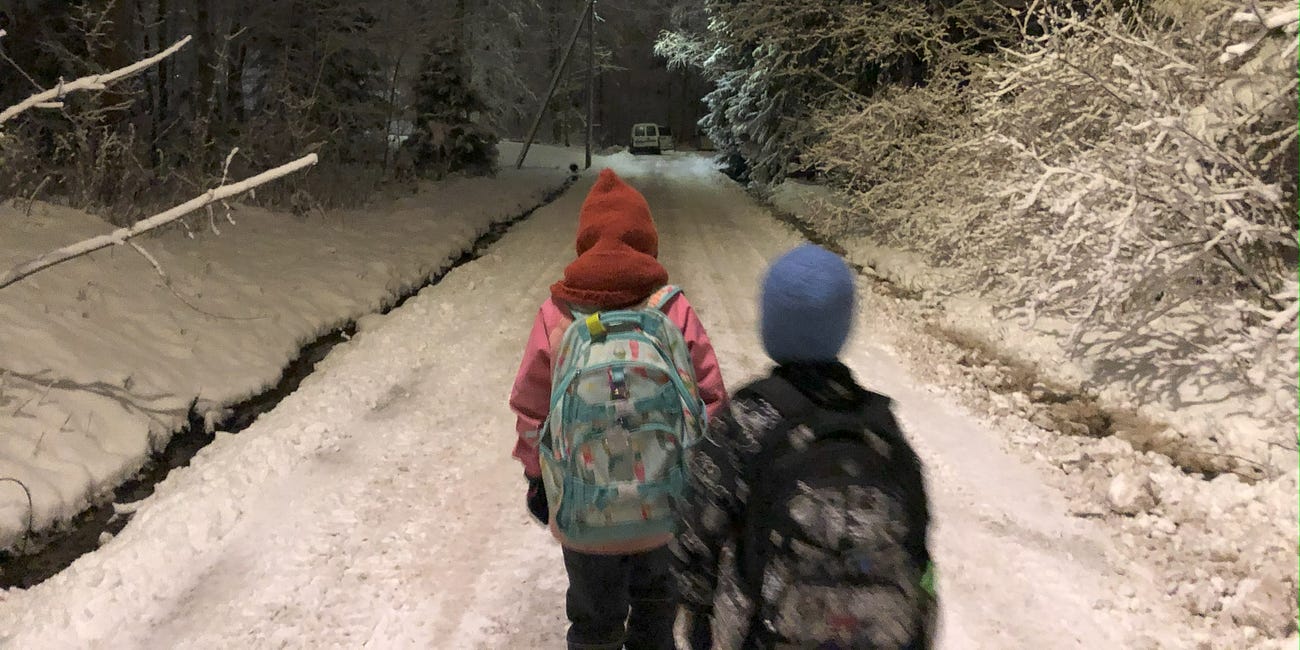

The most notable difference is one that I wrote about very early on in my Substack career (March!) concerning common sight of young children out by themselves, whether walking to/from school, at the store, on the bus, or out at the playground. Yes, children as young as six are capable of walking a mile to school, crossing streets (without crossing guards!), and returning safely at the end of the day. If you missed it, take a minute or two and read it now. It highlights one of the main differences between life in Finland (and in other parts of Europe) and life in the USA:

Life in Finland Part 1: Free-range Children.

Note: In my introductory post I noted that I would be writing about four main topics, one of which is everyday life in Finland. This is the first post in that series, and I plan on coming back to this topic regularly. I hesitate to say how often as I am still finding my rhythm when it comes to writing these posts.

So here we go!

Fourteen Differences About Primary School in Finland

First grade starts the calendar year in which a child turns seven, and students are not expected to be able to read when they start. In practice, this means that students start school one year later than their American counterparts. And although there is a kindergarten curriculum (recently added), it occurs as part of daycare. There is no rush to get the young ones into formal education.

Recess is an important part of every day. It’s at least an hour of a school day that can be substantially shorter than in the USA. And yes- kids go outside and play regardless of the weather. Snow? Rain? Go outside and play! And the playground equipment is fun, too. In the picture below you can see the basket swing, capable of fitting up to 5 or 6 first grades. Two stand and swing it (as the girl in this picture is doing) while the others plop down in the basket, rolling, laughing, and screaming in delight as they go. Recess- or at least breaks- continue into secondary school.

The required hours per week vary by grade level. A first grader has twenty-one blocks of instruction per week; a fifth grader twenty-five blocks. These ‘blocks’ are often called hours but refer to 45 minutes (not one hour) of in-classroom time. This ramp-up continues until middle school (grade 7) at which point students have thirty-one hours per week in the classroom, an amount that stays relatively steady into secondary school.

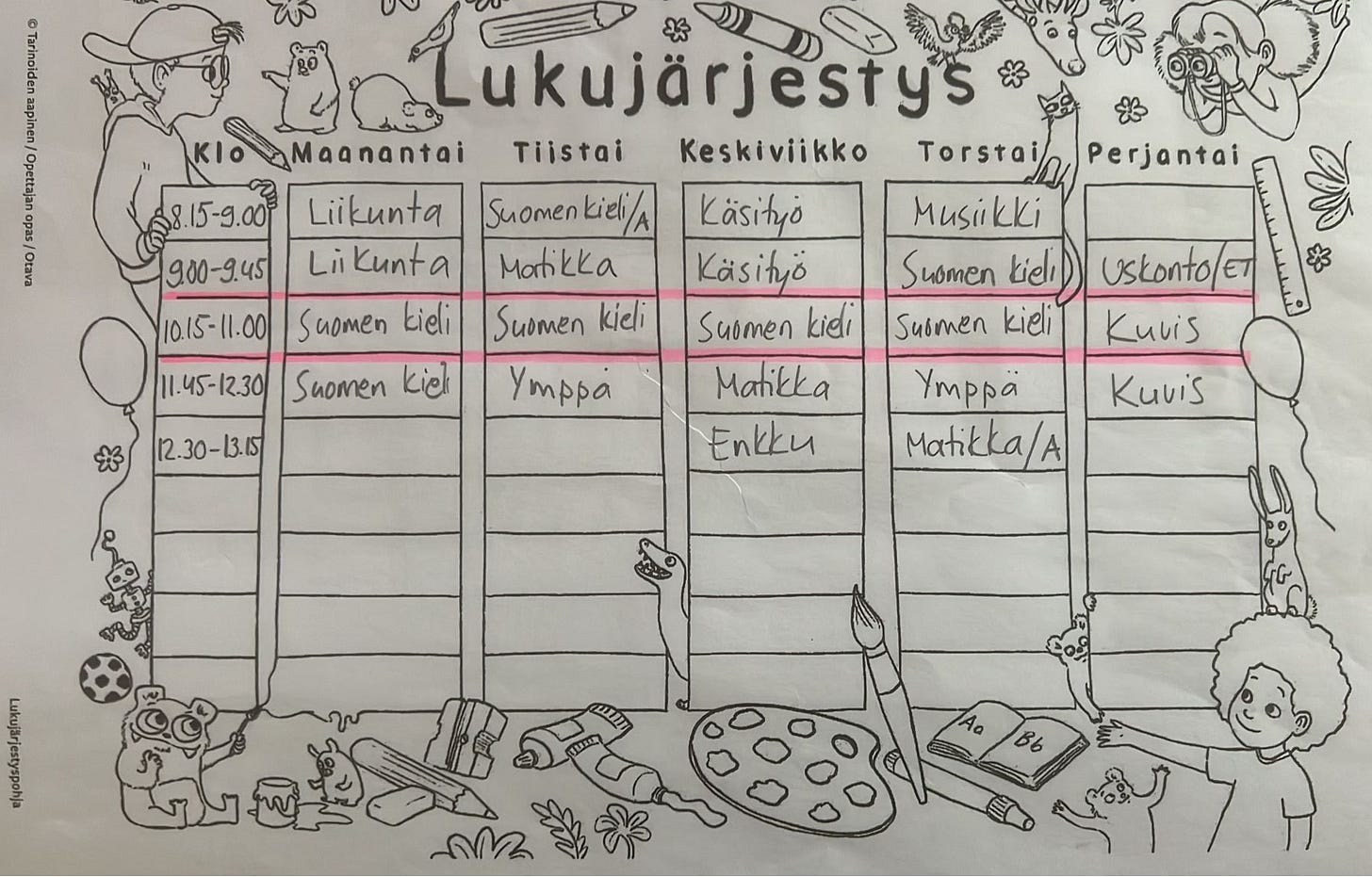

What this means in practice is that every day is different! Below is a sample first grade schedule:

School starts at 0815 Monday-Thursday, but at 0900 on Friday. And school ends varyingly at 1230 or 1315. Note that there is nothing scheduled between 0945 and 1015 (first recess) and 1100 and 1145 (second recess/lunch). Subjects taught: Gym (Liikunta), Finnish (suomen kieli), math (matikka), handcrafts (käsityö), english (enkky), music (musiikki), religion (uskonto), and art (kuvis). There is one additional subject labeled Ymppä, which is short for ympäristöoppi or environment studies. This is a bit hard to explain. It is not environmental science, but rather a multi-disciplinary subject that involves learning about the world around you. In this subject, my first grader is currently in the “I feel well” module where they learn about the importance of exercise and nutrition, and talk about different emotions and how to deal with them. Later, she will learn about the town, how to read a map, learn about the local plants and animals, and then move on to wider geography and history. It’s as if science, civics, and history were taught together in a logical progression. Some of these subjects will split into their own in later grades.

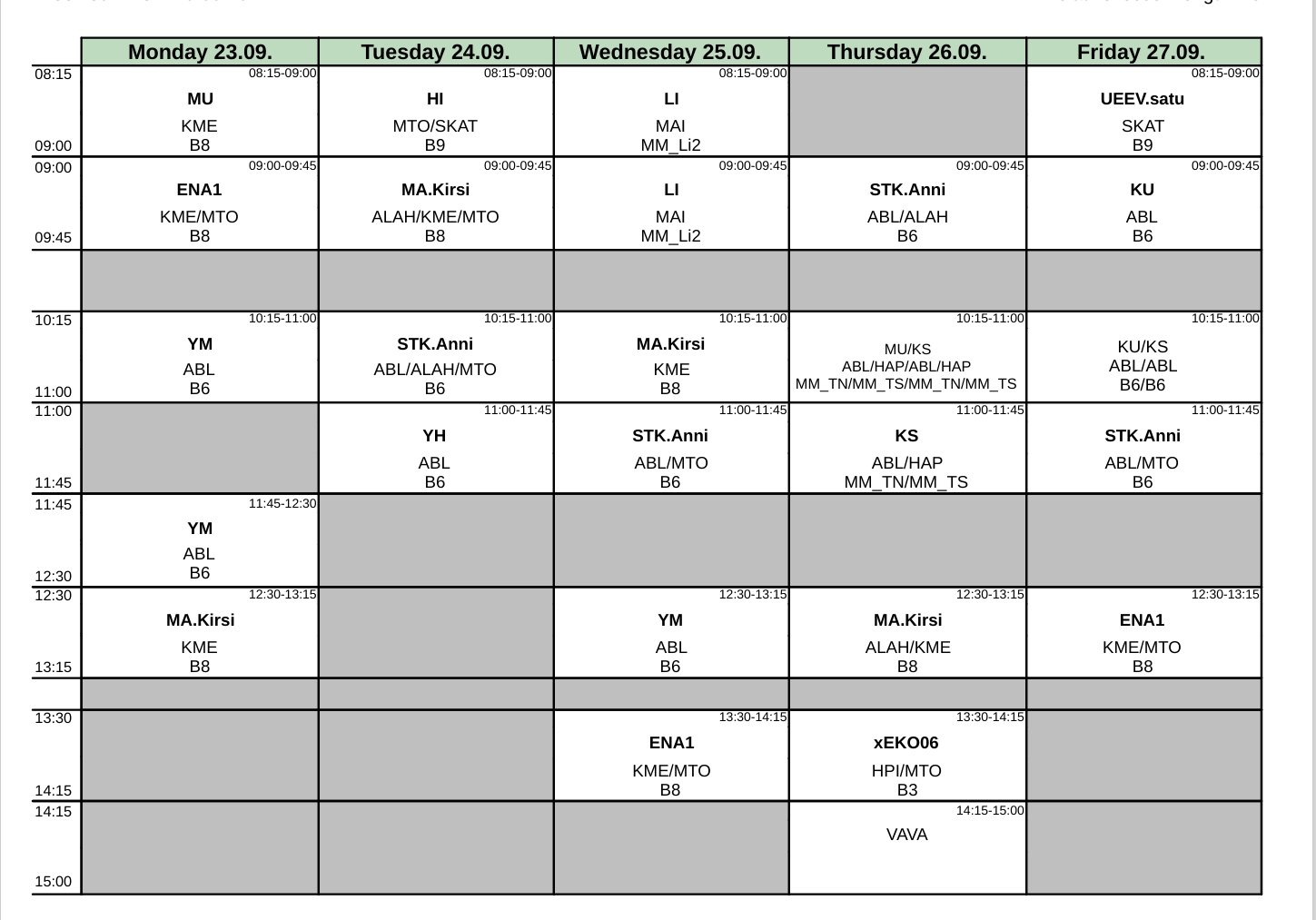

For comparison, here is a fifth-grade schedule:Again, different start and end times. This was one of the biggest surprises when our children first started school, as there is no after school care beyond second grade, and only limited care available for first and second grade. It took us some time to realize that yes, seven-year-olds are okay on their own. For more on that, see the “Free Range Kids” article I linked above.

You read the above paragraph correctly- Religion is taught in public schools. As an officially Lutheran Country, the Evangelical Lutheran faith is part of public education. Parents can opt out, choosing an ethics class or, if there is sufficient demand, a class taught in their own religious tradition. (We’re Catholic. So far, there have not been at least three (that’s the magic number) Catholic families requesting Catholic education in our town. Students attend the local Lutheran Church for Christmas and Easter services, and the school’s Christmas presentation features the birth of Christ. Families can opt out of participation in these events as well, without penalty.

Home economics, woodworking, textiles (including sewing), metalworking, and music are all parts of the curriculum. Math class involves learning everyday finance. One of my daughters was particularly proud of the shovel she made in metalworking, although she was a little too critical (I think) of her welds.

School is very informal; everyone is on a first name basis. The students call even the principal by his or her first name. Teachers and students don’t dress up for school; one year a teacher wore a tuxedo T-shirt for an official meeting with parents. For school photos one year, a teacher wore a bright orange suit. Although it looked perfect normal in the black-and-white yearbook, the class photo we have from that year is quite funny. Just because Finns are considered quiet doesn’t mean that they don’t laugh at themselves.

First graders are assigned a fourth grade kummi. A kummi is like a big brother or big sister- someone of whom the little ones can ask questions or get information concerning school life. Kummi means sponsor, but it is the same base word as that used in godfather/godmother and seems to have the same connotation. A kummi is there to provide guidance, not merely to answer questions. Students have regular meetings with their ‘kummit’ during the school year. This relationship continues throughout elementary school.

Notably, school isn’t the only place where this kind of commuity-mindedness exists. As young people age out of sports (meaning that they no longer have the talent or ability to keep playing competitively), many of them come back to coach the younger teams. Sure, parents help out- but it is normal to see older teenagers or those in their early 20s, who are no longer playing, coaching youth teams in the sports that they love. This is especially true in the less competitive B and C teams (hobby teams, rather than the A side competition team). This attitude helps to foster a sense fo community and encourages the social cohesion that is, in our opinion, a hallmark of the Finnish education system.All materials required by the school (except for a backpack and indoor shoes) are provided by the school. This includes notebooks, pencils, notebook computers (Chromebooks), ice skates, cross-country skis, and other supplies. The idea- and the law- is that attending school must require no out-of-pocket expenses for families.

Schools provide lunch- and it is mandatory. Students are not allowed to bring their own food unless the teacher authorizes a snack for a special occasion. Allowances are made for special diets, but families must inform the school ahead of time. Many teachers still require their students to taste everything. (Yes, teachers are involved in lunch- including teaching (or at least trying to teach) table manners.

Teachers can, and normally do, stay with the same class for several years. My son- in fifth grade- is in his third year with his main teacher. My older children had the same experience with their elementary school teachers. This makes the children comfortable, as they know the teacher, and helps the education process as the teacher knows the strengths and weaknesses of the students from year to year. Teachers also get some variety, as the today’s second grade teacher will be teaching third, fourth, fifth, and maybe sixth grade materials in the coming years.

There are no ‘honors’ classes. Students who pick things up faster help the others (there is a lot of group work) and may get enrichment assignments, but they stay in the same classroom. Children progressing slower, or who need extra help (for example, non-native Finnish speakers) get that help from assistant teachers as part of a plan developed by the teacher, with input from the student and parents.

There are no school team sports. Sports teams for children are sponsored by the town; schools focus on solely on education. Education includes important cultural aspects of Finnish life like using the sauna and important individual sports that support lifetime fitness and outdoor activity such as swimming, ice skating, and cross-country skiing. After school events and clubs may use the school building, but they are generally supported by the town. The education budget strictly belongs to education.

The main task of the school nurse is to conduct annual medical check-ups on all the students, not to treat the sick or injured. The nurse can also administer vaccines and refer students to the doctor.

There you have our ten(ish) differences between American and Finnish primary schools. If you’d like me to expand on any of those differences in a future article, leave a comment or send me a message to let me know.

One note about secondary school:

Those articles that fly around the internet typically say something like ‘the Finnish system doesn’t rely on high-pressure tests.’ That is true, at least in primary school. Teachers use a whole host of methods to evaluate student performance, but the emphasis is on learning, understanding, and being able to use the material- not on passing a test. Tests do become significantly more important as secondary school approaches.

In the Finnish system, elementary school (alakoulu) goes from grades 1-6, middle school (yläkoulu) is grades 7-9, and secondary school (lukio or ammattikoulu) is grades 10-12.

The education system splits for secondary school. Students must apply to the school that they wish to attend for grades 9-12. Some students will pursue an ‘academic track’ high school known as a lukio. Others choose ammattikoulu, equivalent to vocational or professional schools in the USA. Admission to lukio (college prep) or ammattikoulu (practical/vocational) is based on middle school grades (which are based more on tests than earlier) and often an admissions test specific to the school. American friends, please note that the Finnish vocational education is much broader than the ‘Votech’ programs sometimes seen in the USA. It encompasses many fields that require university education in the USA (such as nursing). Anecdotal evidence is that salaries are not notably higher for one track over the other.

Post-secondary education is heavily subsidized, but admission is not guaranteed. University admission is determined solely based on national tests taken by 12th graders and is competitive. The university attendance rate here is significantly smaller than in the USA. There is also post-secondary vocational education at ammattikourkeakoulut, often translated as universities of applied science. These institutions award degrees, but they are not equivalent to a regular university degree.

I’ll save a deep dive into this for a future article. For today, it is sufficient to note that there are indeed high-pressure tests within the Finnish system- they just come later.

Concluding thoughts:

One of the reasons we’ve stayed in Finland is the education system. Immediately before moving to Finland, we lived in the Washington, DC area where children seemed to enter the ‘rat race’ earlier and earlier. Getting into a good pre-school or daycare is something parents were concerned about. Pre-kindergarten programs, with full days in the classroom, began and were encouraged at age 4 and available for half-days at age 3. While these programs are well-meaning, our experience here demonstrated to us that it is not necessary to maximize in-classroom time at a young age. Children can be children; there is no need to rush into the classroom for the best learning experience. Best of all, there is no need for a child to take part in a myriad of after-school activities in order to build College applications.

Outdoor free play is very important in Finland. And we’ve noted that this encourages children to learn important social skills, such as how to get along without adult involvement. By waiting until students are older and ready to learn, and then by ramping up the length and intensity of education, children here are better able to learn and apply what they learn. Having a robust program of hand crafts (sewing, cooking, woodworking, metalworking, etc) allows children to find their skills and learn what they enjoy doing, preparing them to choose a fitting path. And since basic education is the goal of primary school, not simply the means to achieve secondary school, teachers are more concerned with students learning the material than achieving a high grade.

The system here also builds personal responsibility. Children are expected to be responsible, and they rise to the occasion. Fairfax Country Virginia is wrong- six- and seven-year-olds can be responsible and left alone. I often have arguments/discussions with family and friends in the USA, who insist that ‘it isn’t safe’ for children to be left alone in America. I’ll leave you to research your own crime statistics (for now) and we’ll save that discussion for another time. But allow me to note that I’ve lived in nice, safe suburbs and even on military bases within the USA. And in those locations, I still saw parents drive their middle-school children to the bus stop- even if it was only a couple of blocks away.

We like the way that children are treated in Finland. Yes, they do make mistakes. A couple of years ago I allowed one of my teenagers to go to the big city (Helsinki) by herself. She got on the train going in the wrong direction on the way home. But she figured it out- on her own- and this boosted her self-confidence. My youngest, who turns seven in December, no longer needs me to walk to school with her. For now, I do it anyway. But that will change, probably sooner than I want it to. They just grow up so fast.

I hope you enjoyed this break from all of the recent ice breaking coverage. If you did, please hit the like button and let me know if you’d like me to delve a little deeper into any of the specific differences I mentioned above, or feel free to send other suggestions for non-icebreaker topics. Consider sharing with a friend, work colleague, or family member; it takes me some time to research and write these articles, so I’m happy to see them spread far and wide. It’s important to keep this conversation going.

Until next time.

All the Best,

PGR

PS: These are our observations. I’m sure there are some minor factual errors; they are mine. And I look forward from learning more from my Finnish friends and colleagues about post-secondary education as my children approach it.

My dear wife read this article and contributed to its content by offering changes and additions. All typos, grammar errors, and factual errors are my own.

A lot of Americans have forgotten that responsibility isn't taught by schooling, but taught by being given it.

#10 would've killed me, as I never once ate school-provided food, which was uniformly awful.

#12 is the only one which is really wrong. Learning occurs only at the individual level, and group projects do not allow for the strong to help the weak, but allow the weak to skate by on the efforts of the strong. Every group project I've ever been associated with worked that way.

But we were all free-range when we were kids, walking to the school by ourselves, even in first grade.