The Last Days of Corporal Matyola, Part 2: On the Way to the Front, October 1944

Eighty years ago, my Great Uncle and namesake- Corporal Peter Matyola- was part of the replacement system in Europe. Today, we'll look at the winding road that brought him to continental Europe.

Corporal Peter Matyola arrived in England in September of 1944 as one of thousands of replacement soldiers sent to fill the gaps in American units created by the high percentage of casualties born by infantry units since D-Day. He would eventually be assigned to K Company of the 115th Infantry Regiment, part of the 29th Division that had been in combat since it came ashore at Omaha Beach on the 4th of June.

Peter- known as Pinto - was killed in action on the 19th of November. Readers who have been with me from the beginning might remember that I became the first family member to visit his grave back in April. The reverence, respect, and memory of the local Dutch people made a great impression on me. If you haven’t read it, I suggest that you do so now:

Finding My Namesake

On November 19, 1944, a young man from New Jersey named Peter Matyola gave his life for his country on the fields of Germany.

In that post, I suggested that I wanted to write about Pinto’s final days. It’s taken me some time to get to it, but I think writing on or about the 80th anniversary of these events is fitting. This is the second part in this series; the first covered my visit to his grave. This part will cover Pinto’s winding road from Manville, NJ to the replacement depots in Europe.

Peter’s Early Years:

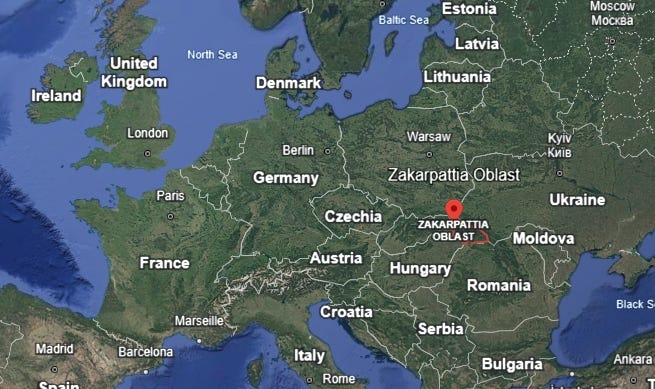

Peter Matyola was born in Manville, New Jersey on June 14, 1919 to parents Michael Matyola and Helen Sidun, ethnic Carpatho-Rusyns immigrants to the USA from what is today the Transcarpathian Oblast in west Ukraine.

Peter had three older brothers (Michael, John, and Charles, all pictured above) and five sisters, among them my grandmother, Anna.

I don’t know many details of his childhood; but he did participate in a 5th grade Christmas show called “A Strike in Santaland” during December 1929. Peter attended two years of high school before joining the depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps, a program designed to supply jobs for young men, in 1936. Peter served several stints in the CCC, likely assisting with the construction of what would later become Fort Dix, NJ.

Registration, Induction, and Basic Training

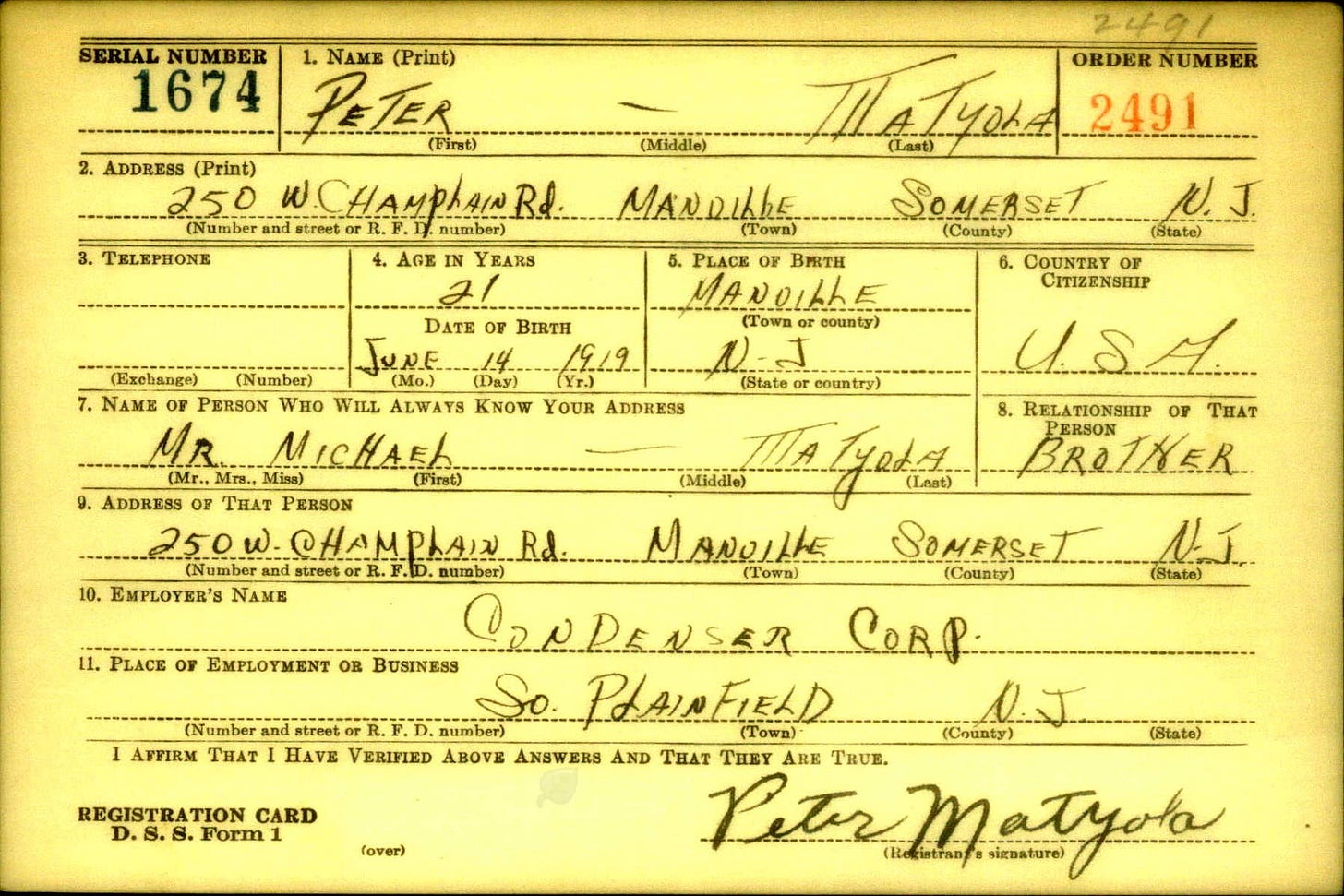

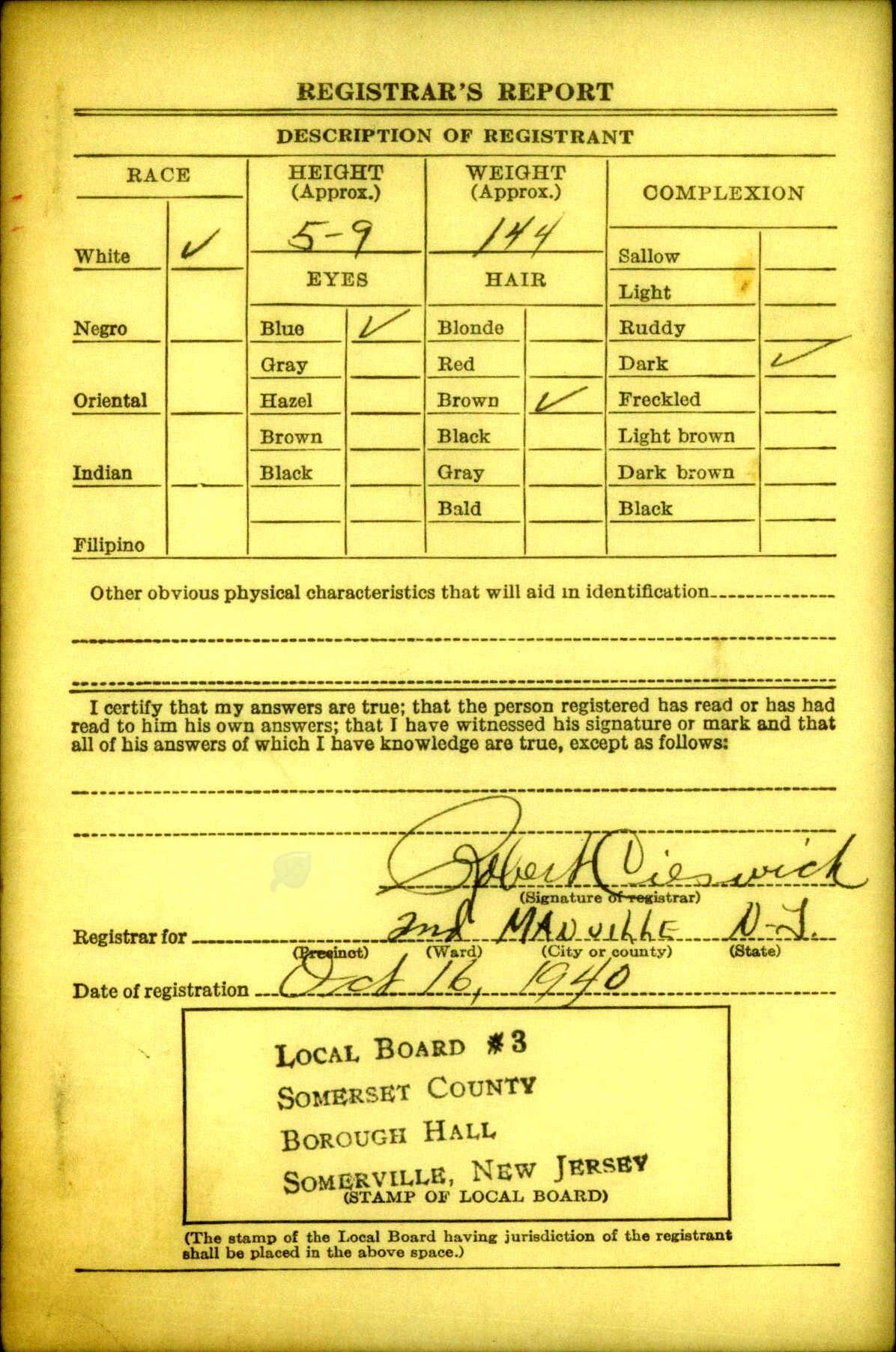

Following passage of the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, the Matyola brothers registered on October 16, 1940. Here is an image of Peter’s registration card, accessed through ancestry.com:

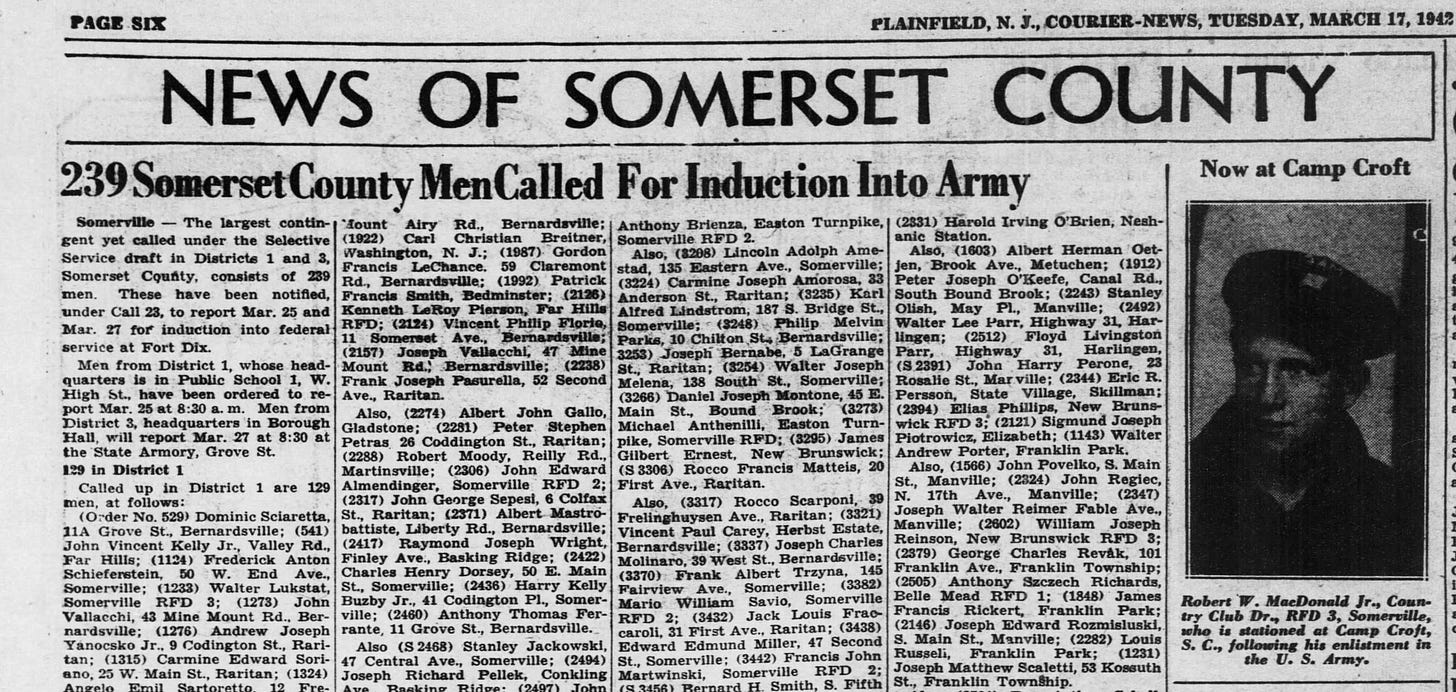

Pinto and his brother Michael (‘Lefty’) were called up in March of 1942:

Pinto and Lefty were inducted into the Army on March 27, 1942, under the following terms:

Enlistment for the duration of the War or other emergency, plus six months, subject to the discretion of the President or otherwise according to law.

Two days before Pinto’s induction, the 305th Infantry Regiment of the 77th Infantry Division was ordered into active military service at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. Pinto would soon join them for boot camp.

I have in my small collection a postcard from Pinto’s boot camp with the 77/305, found at my Great Aunt Hellen’s house:

Text of the postcard:

Hi Ya. This is the real Pinto in the infantry the place I dreaded to land in but I got to make the best of it. Lefty is here and so is Chipp. Its sure warm here. I’ll write soon. So long, Pinto

Second to None: The Story of the 305th Infantry in World War II has an entire chapter on the Fort Jackson experience. Pinto is not named, but I did get an appreciation of the experience through reading it.

Almost exactly sixty-eight years later I’d be at Fort Jackson myself, preparing for an assignment in Djibouti. But that’s another story.

Aviation Cadet Program:

Pinto didn’t stay with the 305th for long. As you read in the post card, he didn’t really want to be in the infantry. Family oral history says that Pinto entered an Aviation Cadet program after bootcamp. Unfortunately, his military service records were destroyed in the 1973 fire at the Military Personnel Records Center, so there is no official documentation. We have this photo, found (with the post card and other photos) at his sister Helen’s house. Based on the type of aircraft (an L-4 Grasshopper, used in ‘dead stick’ training for glider pilots) and the timing of his assignment (and later re-assignment), I believe that Pinto joined the glider pilot training program.

Throughout 1942, the U.S. Army Air Forces revised upwards the estimated number of glider pilots that would be needed. From an initial goal of 1,000 glider pilots set in February, the requirement grew to a total of 6,000 in May, with a goal of training them all by the end of 1942. In order to try and meet this goal, the Army Air Forces kept loosening the requirements. By June, “applicants lacking previous aerial experience would be accepted for training provided they possessed the other requisite qualification1.” Thus all 18–32-year-olds who met the Class I Physical standards were then eligible to enter this program. It was in this push that I believe Pinto signed up.

By the end of July problems with finding enough training aircraft reduced the expectation for 1942 (3,000 total trained instead of 6,000) but set the goal of an additional 12,000 glider pilots completing training in 1943.

By February of 1943, a realistic consideration of the priority for production of war material (gliders were low on the list) and other changes in strategy greatly reduced the AAF’s projected requirements down to 4,054 glider pilots in total. As there were an estimated 10,000 students in the glider pilot pipeline at that time, thousands of trainees were reassigned. Many who came from the regular Army to the AAF were sent back. I believe that this is what happened to Pino.

However in early 1943 his previous unit, the 305th Infantry Regiment, 77th Infantry Division, was already in the middle of its advanced training. So instead of going back Pinto now found himself with the 297th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division as it was finishing up its basic training at Fort Jackson. Pinto was with the 297th from 1943 until mid-1944, completing its advanced training (that included winter maneuvers in the Tennessee mountains) and moving with it to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. While at Bragg, Pinto was awarded the Expert Infantryman’s Badge.

On to Europe and an Uncertain Future

Meanwhile, mounting U.S. Army casualties in Europe- particularly riflemen- led to a scramble to replace these higher-than-anticipated losses. For September of 1944, the Ground Forces Replacement System requested 36,750 replacements for the European Theater of Operations, nearly all of them infantry soldiers. But the War Department could not provide enough infantrymen already designated as replacements, so it stripped some personnel from trained infantry divisions still in the USA. This would delay the deployment of these divisions overseas but was considered necessary.

Pinto was selected as one of these replacements from the 100th infantry division and was sent first to England (in September 1944) and then to France two weeks later. In early October, he was probably not sure where he would end up.

Coming Next:

Events that would take place concerning the 115th Infantry Regiment on October 4, 1944, determined Pinto’s fate. We will pick up with that story in Part 2.

A special thanks to my cousin Gary, who, along with my Uncle John did a lot of the initial family research that pointed me in the right direction.

If you’d like to learn more about any of the topics I’ve listed, let me know and I’ll come back to it later. I learned a lot more than I can fit in these articles and would be glad to go into more depth on the phased mobilization of units and personnel, the Glider Pilot Training program, or the Replacement Program in future posts.

I’ve included a list of my references below for those of you who are researching your own family members or would just like more information.

Until next time, thanks for reading, subscribing, and spreading the word.

If you liked this article, press the heart. Subscribe so that you won’t miss part two or any of my other updates concerning icebreakers or life in Finland. Lastly, please share with a friend or seven who might also appreciate these articles.

All the Best,

PGR

For more information:

Enlistment records can be found through the National Archives. Seach by name here.

For information on the Glider Pilot Training Program, see the Army Air Forces Historical Studies, the Glider Pilot Training Program 1941-1943 (Part I) and Part II.

For more information on the replacement program, see Erik Klinek’s 2014 Dissertation, The Army’s Orphans: The United States Army Replacement System in the European Campaign, 1944-1945.

For information on the 305th Infantry Regiment in World War II, see Second to None: The Story of the 305th Infantry in World War II.

For information on the 100th Infantry Division, see The Story of the Century.

Ancestry.com has access to draft registration card images and other useful information for those of you trying to learn about relatives.

Thanks for this Pete! The links to archival data are especially appreciated.