Analyzing the Arctic Security Cutter Request for Information

Assessing what the responses to the RFI might have looked like, based solely on publicly available information.

Note: The responses to the RFI will most likely remain private, and there have undoubtedly been non-public responses. For the purposes of this analysis, I am only considering publicly available information.

The U.S. Coast Guard issued a Request for Information for its ‘Arctic Security Cutter’ program on April 11th. I went through the RFI and gave my initial thoughts about it here:

As a quick refresher, this is what the RFI asks for:

The purpose of this RFI is to increase the USCG’s understanding of the current status and capability of both the U.S. and broader international maritime industrial base as it pertains to existing icebreaking capable vessels or vessel designs that are ready for construction or already in production.

To increase this understanding, the USCG asks for two specific things. First:

Specifically, the USCG seeks to understand what existing vessels or production ready vessel designs satisfy or closely satisfy the below preliminary capability parameters.

Second:

Additionally, the USCG would like to gain insight on recently proven execution and build strategies as well as the current capability and availability of global shipyards that could support the construction and subsequent launch of an existing icebreaking capable vessel design within THIRTY-SIX (36) months of a contract award date.

I thought it would be useful to look at publicly available information to get a picture of what the RFI responses might have looked like. Let’s start by looking at some existing icebreaking vessels/designs.

Selected Icebreaking Vessels/Designs

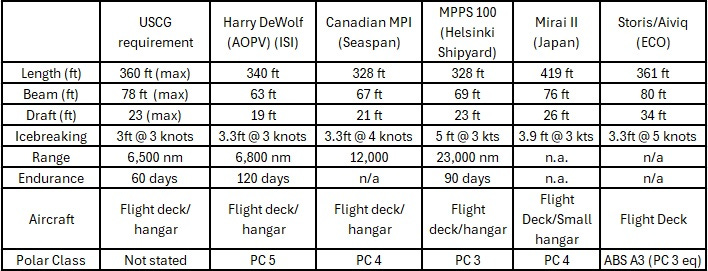

This chart summarizes the vessels/designs that I selected and compares them with the U.S. Coast Guard’s “Vessel Preliminary Capability Parameters” as listed in the RFI.

I chose these vessels/vessel designs for different reasons.

Canada’s Harry DeWolf Class Arctic Offshore Patrol Vessels (AOPVs): currently in production by Irving Shipbuilding Incorporated. Vessels meet all of the listed requirements.

Canada’s Multi-Purpose Icebreaker (MPI, formerly known as the Multi-Purpose Vessel): Modern design that meets all of the listed requirements. The first flight of six vessels (of a planned sixteen) are scheduled to be built by Seaspan at their Vancouver shipyard.

Davie/Helsinki Shipyard’s MPPS-100: Fourth generation of a successful icebreaker design that meets all of listed requirements. Before this design was announced last week, I was planning on including Helsinki Shipyard’s third generation of this design, Helsinki Shipyard’s NB (New Build) 514.

Japan’s Mirai II: I added this vessel after reading that Japan’s Prime Minister recently suggested “the joint development of icebreakers to be a focal point in the Japan-U.S. tariff negotiations.” The vessel Mirai II, currently under construction, is the only icebreaker to be built in Japan in quite some time.

United Shipbuilding Alliance’s Storis: Two U.S. shipbuilders, Bollinger and Edison Chouest Offshore (ECO) have created the “United Shipbuilding Alliance” and are using the USCGC Storis, (formerly known as Aiviq) as a reference vessel to support their claim that they can build an icebreaker in less than three years. It isn’t clear if they intend to design a new vessel based on Storis/Aiviq (or ECO’s planned, but never built, follow on PC3 icebreaking AHTS) or to build a different design. More on that later.

Canada’s Harry DeWolf Class Arctic Offshore Patrol Vessel

Irving Shipbuilding Incorporated (ISI) of Canada has already delivered five of six planned vessels for the Royal Canadian Navy, with the sixth expected this year. Two more of the vessels are under construction for the Canadian Coast Guard. Construction of the most recently delivered vessel, Frédérick Rolette, took approximately 39 months (May 2021-August 2024).

But just because the AOPVs meet the listed requirements does not mean that it is the right vessel for the job. In 2023, the U.S. Coast Guard conducted a fleet mix analysis (FMA) that determined it needed a total of eight or nine polar icebreakers, including four or five heavy icebreakers and four or five medium polar icebreakers. Icebreakers, or ice-capable vessels, perform many different missions. At this time, the FMA is not public. Without more information from the U.S. Coast Guard about how and where it intends to use the Arctic Security Cutter, I can’t tell how suitable the OPV would be for the ‘medium icebreaker’ role.

There are some hints, though. Last year, U.S. Coast Guard Capt. William Woityra, an experienced polar icebreaker officer and former Commanding Officer of the heavy icebreaker Polar Star, collaborated with Adam Lajeunesse, PhD, on an article for the Canadian Maritime Security Network that supported acquiring one or more AOPVs as a ‘gap-filling’ measure for the U.S. Coast Guard. The article also noted characteristics that make the AOPVs unsuitable as full time Arctic Security Cutters (italics mine):

The AOPVs offer the USCG an interesting opportunity. They are not icebreakers in the traditional sense and not the medium icebreakers that are called for in the Coast Guard’s Fleet Mix Analysis. While they can break 1-1.5 metres of ice at three knots (similar to USCGC Healy), they have only 40% of the displacement and 64% of the horsepower. They are PC-5 ships (with a PC-4 bow), designed for patrol in icy waters, rather than icebreaking through heavy pack ice. They are also not designed for operations in heavy concentrations of old ice.

Canadian Coast Guard Multi-Purpose Icebreaker (MPI)

Canadian shipbuilder Seaspan is actively pitching this design for the Arctic Security Cutter.

As I told the Wall Street Journal, “wherever you look in icebreaking, you’ll find a Finn.” In this case, Finnish design firm Aker Arctic was responsible for concept design development. In preparation for this article, I had an e-mail exchange with Dave Hargreaves, Seaspan’s Senior Vice President for Strategy, Business Development, and Communication. He provided me the following updated capabilities of the MPI:

• Open water speed: 16.0 knots

• Speed in 1.0m ice: 4.0 knots

• Max ice thickness at 3 knots: 1.3m

• Range at 10 knots: 13,500 nautical miles. Note that it is about 3,000 nautical miles from Seattle to northern Alaska, so the 6,000 nm range in the RFI is likely insufficient for meaningful operations in the Arctic.

• Flight operability and deck operations in Sea State 5, compliance with NATO STANAG 4154 requirements for seakeeping

In comparing the MPI with the AOPV, he added:

These are both very capable vessels that meet the USCG requirements, however, they have very different missions. The MPI is a real icebreaker with broad capabilities to fulfill an icebreaking mission.

Seaspan plans on building sixteen of these MPIs for the Canadian Coast Guard, with construction for the first flight of six scheduled to begin in 2027. Seaspan says, though, that the MPI design will be ‘ready to build in Q4 of this year.’ As for what ‘build ready’ means, Dave continues:

It’s certainly true that the “readiness” definition it is highly dependent on the shipyard. We typically model to a much higher level of detail than many other yards, largely a result of the higher level of change control and production detailing needed for NSS projects here in Canada. We expect to complete functional design with the Canadian Coast Guard this summer. However, we have reviewed the design in detail with a range of shipyards and the feedback has been that the current production model is of a sufficient level of detail to begin the pre-production process immediately (i.e. “build ready” for them), with any detailing for their specific production system and manufacturing drawings able to be completed by Q4 2025 (this year).

Davie/Helsinki Shipyard MPPS-100

Davie unveiled this vessel design at the end of May during CANSEC, Canada’s main defense trade show. I had the opportunity to visit Helsinki Shipyard about a week later for a short discussion of this design and its history. Contrary to what may have been reported elsewhere, the design was not specifically created in response to the U.S. Coast Guard’s RFI.

Rather, the design work began last year in order to meet forecasted demands from both Navies and Coast Guards for polar capable vessels. This points to one aspect of the vessel- it can be further customized for a specific mission set, whether it be by adding scientific research stations or reserving power, space, and weight for sensors or weapons systems.

Seaspan’s MPI and Helsinki’s MPPS can both trace their design lineage back to the FESCO Sakhalin, an icebreaker built for the Far East Shipping Company (FESCO) delivered by Helsinki Shipyard in 2005. Aker Arctic has a good article about how this design came about titled “The Father of Modern Icebreakers: FESCO Sakhalin.”

Helsinki Shipyard continued the design evolution, with the second-generation design bringing a new engine room arrangement and engine configuration. But it is the third generation where things get interesting. The four third-generation vessels were all built on the same (improved) platform but were customized for specific roles. Some had a moon pool, some were designed to handle additional fuel, etc.

This is the same idea behind the (fourth generation FESCO family) MPPS- an improved platform, with increased capabilities and survivability, but with flexible arrangements according to the customer’s needs.

Japan’s Mirai II

Japan has one icebreaking vessel under construction, its Arctic Research Vessel Mirai II. Although the Japanese prime minister recently claimed that Japan had an expertise in building icebreakers, there doesn’t seem to be much to this claim, as icebreakers are about a once-in-a-generation build for Japan.

Mirai II will be too large to fit the U.S. Coast Guard’s needs, and is being specifically designed to support scientific research. It seems she will have a flight deck and a small helicopter hangar. As for build time, work began in 2021 with delivery expected in 2026 or 2027- a longer build time than desired, and that would be without modification.

This design is not suitable as an ASC without modification.

USCGC Storis (Ex Aiviq) (or planned follow-on AHTS)

Storis/Aiviq has a spot on my list because two American Shipbuilders, Bollinger and Edison Chouest Offshore (ECO), are using it as a ‘reference’ vessel to demonstrate that they can build icebreakers within three years.

From a Bollinger press release:

The viability and effectiveness of commercial vessel construction for national security purposes have been firmly demonstrated through the recent acquisition of the USCGC STORIS (WAGB-21) [ex – M/V AIVIQ]. The STORIS is an American-built icebreaker designed for Arctic conditions and delivered in under three years.

Storis/Aiviq was designed and built first and foremost as an Anchor Handling Tug Supply Vessel (AHTS) to support oil exploration. Storis/Aiviq does not meet the requirements of the ASC RFI; the U.S. Coast Guard bought her because she was the only commercial icebreaker on the market. And as a bridging strategy, this makes sense, even though it is apparently going to cost about $500 million to operate, modify, and maintain during Storis for her first seven years of operations. (Source: GAO report) So does it make sense to use the Storis/Aiviq (or any AHTS) as a basis for the Arctic Security Cutter?

The short answer is no. You can read more about the reasons why in my article here, and an even more critical one by McKenzie Funk in ProPublica.

Design Summary

That leaves three viable designs that we know of: Seaspan’s MPI, ISI’s Harry DeWolf-class AOPV, and Davie/Helsinki Shipyard’s MPPS-100.

Now the Hard Part- Actually Building an Icebreaker in 36 Months

There are basically two options for the shipyards that own these designs. They can build the vessels themselves, or they could sell or license the design to be built by another shipyard. We’ll first look at the possibility of shipyards building their own designs:

In-House Build:

Harry DeWolf class AOPV:

According to Canada’s National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS), following production of the last two vessels for the Canadian Coast Guard, ISI is scheduled to begin producing River Class Destroyers for the Royal Canadian Navy:

An obvious answer for the USCG would be to acquire an AOPV from the hot production line in Halifax. The final vessel in this class is intended to be delivered to the Canadian Coast Guard in 2027. Meanwhile, full-rate production of the River-class destroyers for the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) is slated to begin in 2025. Shipyard space is therefore tight; however, because ISI has become so effective at producing the AOPV, there is room to add one additional vessel to the schedule without impacting the construction of the River class. (Lajeunesse/Woityra article)

With additional delays to the River class, one vessel could become two, but probably not the five that the U.S. Coast Guard is asking for. And as hinted earlier, these might not be the types of vessels that the U.S. Coast Guard needs. And even ISI, with a hot production line, is taking longer than 36 months to build an AOPV.

Seaspan’s Multi-Purpose Icebreaker (MPI):

Seaspan’s Vancouver Shipyard is at capacity through approximately 2029. While they will begin building MPIs for the Canadian Coast Guard, there is no room to build one for the U.S. Coast Guard in the relevant timeframe.

Davie/Helsinki Shipyard’s MPPS-100:

During my recent visit to Helsinki Shipyard, I was assured that they have space in their order book to build these vessels for the U.S. Coast Guard. When I asked approximately how long it would take to build these vessels- from order placement to delivery- those present declined to give me a direct answer.

Smiling, Kim Salmi, the CEO, asked me to look at the normal interval between order and delivery of similar vessels at the shipyard.

He specifically mentioned the build timelines of the second generation FESCO family vessels (NB 506 and 507). The order for both was placed in December of 2010. NB 506 was delivered in December 2012 (24 months after order), and NB 507 was delivered in April 2013 (28 months from order to delivery).

Four of the third-generation icebreakers- each one slightly differently- were ordered in May of 2014. The first one was delivered in March of 2017, 34 months after the order. Amazingly, two additional vessels were delivered in 2017 (July and October), and the fourth in February of 2018. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, that is four vessels in less than four years1.

Yes, it is a new design. But it doesn’t take years for Helsinki Shipyard to get a design ready for building. If you want to understand how Helsinki Shipyard can do this, read:

How to Build an Icebreaker in Three Years

Building icebreakers. It shouldn’t be that hard. European shipyards, especially those located in Finland, routinely design and build these specialized ships for a variety of purposes. In North America, however, it’s a different story. Both the U.S. and Canada have struggled over the past decade with delays in designing and building their own polar i…

And now, with Davie announcing its intention to acquire two Texas shipyards, there is the possibility that an order placed with Davie could eventually involve Helsinki Shipyard sharing the work with these American shipyards (similar to the current deal to build a PC2 icebreaker for the Canadian Coast Guard in both Helsinki and Quebec). However, Davie first needs to finish the acquisition process for the Texas shipyards and complete extensive upgrades.

Build in Another Shipyard

This is exactly what Seaspan is trying to do with their MPI. From my e-mail exchange with Dave Hargreaves:

As a result [of our lack of capacity] we are looking to cooperate with another shipyard (either in the US or outside depending on what the US Government decides) to build our Multi-Purpose Icebreaker (MPI) design. We would sell our design (we own it) to the shipyard or to the USCG depending on their desired contract structure and provide any support services (engineering or otherwise) for that design. We are in discussion with a number of shipyards to support them with this concept.

But which shipyard? There are very few that have recently built an icebreaker in less than three years.

Bollinger/Edison Chouest Offshore “United Shipbuilding Alliance”

Their only reference for an icebreaking vessel built in less than 36 months is Storis/Aiviq, which was ordered in July of 2009 and completed in April of 2012.

But as noted above, Storis/Aiviq is not the ideal vessel for the U.S. Coast Guard. One of my readers, who was in a position at the time to be familiar with Storis/Aiviq’s original design and construction, noted:

The Edison shipyard was unable to bend thick plates in three-dimensional form, so the vessel is made from only two-dimensionally bent plates.

Could they build a more modern design like Canada’s MPI? Perhaps. Would I bet on them doing so in less than three years? No.

Seaspan’s own plan for the first MPI is to begin construction in 2027 and deliver in 2031- approximately four years. I cannot see how the “USA” could do better than the design yard in building these vessels.

Rauma Marine Constructions

Although the most recent polar class vessel built in Rauma was the S.A. Agulhas II (a South African icebreaking supply/research vessel), delivered in 2012, the Rauma shipyard (although under previous ownership) built the multi-purpose icebreakers Nordica and Fennica for Finland- all in less than 36 months. Today, RMC is building ice-capable corvettes for the Finnish Navy. During my recent visit RMC highlighted how it is maintaining its capabilities to work with thick steel so that it is ready to build icebreakers again.

As I wrote back in April,

Similar to Helsinki, RMC says they can build an icebreaker for the U.S. Coast Guard within three years of contract signing. The first step would be a letter of intent followed by about six months of concept design in which the shipyard, design firm, and U.S. Coast Guard would work to define the requirements and create the concept design. At the end of that approximate six-month period, RMC would sign a build contract. Three years later, the U.S. Coast Guard would have one (or more) icebreakers delivered. With the launch of the first corvette approaching, RMC leadership tells me that if the U.S. acts now, it has the resources to begin work this summer.

My full article is here:

Building MPIs at RMC is an interesting idea, but I have no idea if that is actually under consideration.

Korean Shipyards:

From 2016-2019, under its previous name of Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering (or simply DSME), Hanwha Ocean built 15 icebreaking LNG carriers for use along Russia’s Northern Sea Route (NSR). These are large vessels (displacing more than 150,000 tons) and they were built relatively quickly. A contributing factor to this was the concept design, based on decades of research, completed by Aker Arctic. Specific design work in support of these Yamal LNG tankers began in 2010, but much had been done before hand.

Hanwha additionally built six more advanced LNG tankers for various clients to support Russia’s LNG 2 project, but these vessels have not been delivered because of sanctions.

When it comes to building smaller icebreaking vessels in small quantities, South Korean shipyards haven’t done as well. South Korea’s sole icebreaker, Araon, is a research vessel built in 2009. South Korea’s current icebreaker project- the Next Generation Icebreaker- was first funded in 2022 with an expected delivery in 2026. Delays have already pushed its planned delivery to beyond 2027. The South Korean Government just increased the budget allocation for the project, allowing bidding for construction to begin in May.

From what I’ve heard and read, South Korean shipyards excel at building large quantities of vessels (as in the 15+6 LNG tankers). They do not specialize in small vessel runs (such as icebreakers).

You can read more about the LNG tankers in this article that I wrote last year.

Hanwha and Philly Shipyard: The Icebreaking Connection

Last week brought yet more news surrounding possible international collaboration in building icebreakers as both the White House and Davie released statements about foreign investment in U.S. shipyards. We will look at the July 29th a…

Vard Shipyard:

Vard has built several Polar Class cruise vessels with the hulls being built Vard’s Tulcea, Romania shipyard and finished in Norway. This includes NATO’s most capable icebreaker, the PC2 icebreaking Cruise Ship Le Commandant Charcot as well as two PC6 cruise ships. One of the PC6 vessels, Viking Octantis, was delivered about 3.5 years after being ordered. Her sister ship, Viking Polaris, was delivered about nine months later. Charcot, being a more complicated vessel, also took about 3.5 years from build contract- but that that contract was awarded after two years of design work. I don’t know what Vard’s order book looks like at the moment, but they may be a contender to build a MPI or other design.

Thoughts and Comments

I’m sure that the U.S. Coast Guard received many responses to this RFI from both designers and shipbuilders, with only some of them being announced publicly.

Looking at the public information, it seems that there are only two viable options if the U.S. Coast Guard is indeed looking for existing designs only:

Build MPPS-100 vessels at Helsinki Shipyard

License Canada’s MPI or Harry DeWolf OPV to different shipyard.

When it comes to building a modern icebreaker in under three years, there is only one shipyard with a current reference (i.e. in the past ten years)- and that is Helsinki Shipyard. RMC is the other shipyard with such a reference, but that dates back to 2012, as does ECO’s construction of the Storis/Aiviq2. As noted above, though, RMC is actively working to maintain its capability to build icebreakers.

Licensing the MPI or AOPV to RMC is certainly an interesting idea, and it may be under discussion. Seaspan is actively touting its MPI as a suitable vessel for the U.S. Coast Guard, and RMC is reportedly in discussions with the U.S. Coast Guard as well.

Building MPIs or AOPVs in Korea might also be possible but could provide an interesting optic if a Korean shipyard delivers MPIs at a faster rate and at a lower cost than Seaspan itself. Then again, the more organizations involved, the more complicated the administrative processes will be leading up to actual shipbuilding.

As far as Davie/Helsinki Shipyard goes, their only reply to me when I ask them about discussions with the U.S. Coast Guard continues to be a very clear NO COMMENT.

We’ll just have to wait and see what happens.

Until next time-

All the Best,

PGR

Edited to clarify that the quoted figure of approximately $500 million for Storis includes not only modifications, but operations and maintenance for the first seven years.

Note that all seven of the FESCO family vessels were built after Helsinki Shipyard sold off its steel production facility. I’ve been told by many within the Finnish shipbuilding industry that Helsinki Shipyard has developed a tight network of suppliers who are ready to meet its needs.

As noted above, I do not think Storis/Aiviq is a suitable reference vessel.