Don't Double Down on the Polar Security Cutter

Believing that U.S. Coast Guard icebreaking is somehow 'back on track' would be a mistake. The U.S. should look to proven allied shipbuilders to meet its short- and medium-term strategic needs.

In December, the U.S. Coast Guard reported that actual construction work had finally begun on the first Polar Security Cutter, with delivery expected in 2030. Notably, according to the original 2019 contract, the first ship was expected to already be complete (in 2024). The program suffered a number of setbacks, including significant design problems. Despite the program’s history, I’ve heard that some are now optimistic that the PSC program is on track. Based on experience- and current warnings from the GAO- that optimism is a mistake.

In this article, I take a look at the PSC program and compare it to other icebreaker programs that ran at the same time and produced many quality vessels. My conclusion, as noted above, is that the U.S. Coast Guard will not get the ships it needs in a timeframe that matters without help from our allies and partners.

This article has many charts that make it too long for e-mail, so please click through to read the whole piece. Thank you.

The Polar Security Cutter Program: Background

The Polar Security Cutter (PSC) Program began as the Heavy Icebreaker Program in FY 2013 with the appropriation of $8 million dollars to “initiate survey and design activities for a new Coast Guard polar icebreaker.” The program aims to acquire three Polar Class 2 icebreakers for the U.S. Coast Guard. Here is how the program has been funded since the beginning:

Funding Notes:

The initial plan presented by the U.S. Coast Guard in 2013 sought $860 million over five years with a goal of taking possession of the first ship within a decade. But the subsequent funding requests in FY 2014 and FY 2015 were far less than anticipated, with the FY 2016 request signaling a reduction of the five-year amount by 81%. The Congressional Research Service reported that this reduction was because the Obama administration had at some point internally deferred construction until FY 2022. But in late 2015, the Obama administration reversed itself and began to push again for construction to begin in FY 2020.

In FY 2015, Congress did not appropriate the U.S. Coast Guard’s requested $6 million, as the U.S. Coast Guard had obligated less than $2 million of the already appropriated $10 million.

From FY 2016 to FY 2020, Congress generally gave the U.S. Coast Guard more money than requested in the budget in an effort to accelerate the program. Congressional hearings from this time period feature Members of Congress offering more money than the U.S. Coast Guard wants.

By the end of FY 2021, the U.S. Coast Guard considered the first two vessels to be ‘fully funded’ with a total of $1.6 billion appropriated.

After FY 2021, Congress tended to not give the U.S. Coast Guard its full request for the PSC Program, as these requests were for long lead items associated with the third vessel.

Important Contract dates:

February 22, 2017: Five fixed-price contracts for heavy polar icebreaker design studies and analysis were awarded to Bollinger, Fincantieri, General Dynamics/National Steel, Huntington Ingalls, and VT Halter. Total cost: $20 million.

April 23, 2019: A $745.9 million fixed-price contract was awarded for construction of first PSC to VT Halter. Construction was to begin in 2021 with vessel delivery in 2024. It contained financial incentives for early delivery, and was hoped the vessel would be complete in 2023.

December 29, 2021: A $552.7 million Fixed Price incentive option was awarded to VT Halter for construction of a second PSC.

February 2024: U.S. Coast Guard leadership notified Congress that the first PSC would experience cost growth in excess of 20 percent and a schedule delay in excess of one year.

Currently: The U.S. Coast Guard and Bollinger are working to revise the cost and schedule estimates for the PSC. The U.S. Coast Guard originally promised this update to Congress by the end of 2024 but has not yet delivered it (or at least it is not publicly available).

Schedule:

Here is a chart showing the projected delivery date of the first PSC has changed over the years. Note the rapid changes in recent years (a six-year delay announced between 2021 and 2024!), as the problems with the detailed design and construction came to light. It is still early in 2025; more delays may be coming as actual construction begins.

There is no point including the second and third vessels. Originally, the U.S. Coast Guard assumed that additional ships would be delivered each year after the first. In more recent Congressional Hearings, the number is now two years between vessels.

There are many examples of unwarranted optimism along the way. I will cite but two of them:

June 18, 2021. Production work- i.e. steel cutting- was supposed to start earlier in the year but by this date it was known that it would start at least one year late. Yet, the U.S. Coast Guard still hoped that production work will begin in 2021 and remained optimistic for delivery in 2024:

Cutting of steel on the first new Coast Guard heavy polar icebreaker could happen in the coming months, which is close to a year later than originally expected, but the forecast to start production still appears hazy.

Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Karl Schultz said on Monday [June 28] that “They tell me we should be cutting steel on the first articles here in the coming months, so, hopefully there is steel cutting this year and contractually…we’re on contract for that ship [in] late ’24.”…

The Coast Guard originally had expected the first PSC to be delivered in the first half of 2024 the potential to accelerate delivery into late 2023. That appears unlikely now given that the start of construction appears to be about a year behind schedule. (Cal Biesecker, “Construction Of First Polar Security Cutter Slipping,” Defense Daily, June 28, 2021)

October 19, 2021. Delivery has now slipped to 2025, but it should slip no further as the U.S. Coast Guard has “negotiated a consolidated contract action that definitizes COVID-19 delays and rebaselines the delivery schedule by 12 months”:

Delivery of the first new Coast Guard heavy polar icebreaker has slipped a year to 2025 due to the fact that it’s been 45 years since the last heavy icebreaker was built in the U.S. and impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, Adm. Karl Schultz, the service’s commandant, said on Tuesday [October 19]….

Schultz said that COVID “complications” have hampered “international collaboration” on PSC ship construction, noting that the program is ambitious and “on a compressed timeline.”

A Coast Guard spokesman told Defense Daily in an email reply to questions that infection rates and travel restrictions due to COVID “significantly affected Halter Marine’s ship design efforts and subcontractor integration, resulting in unavoidable delays. COVID-19 was particularly impactful to HMI’s efforts to hire and maintain staffing levels across multiple occupation categories (labor, management, and engineering) and hindered collaboration with its ship design subcontractors, many of whom are based internationally and were significantly affected by early COVID-19 restrictions.”

The spokesman added that “The Coast Guard and Navy Integrated Program Office recently negotiated a consolidated contract action that definitizes COVID-19 delays and rebaselines the delivery schedule by 12 months.” Still, the program remains on track to begin operations in 2027 with Operation Deep Freeze, he said. (Cal Biesecker, “Coast Guard Commandant Confirms Delay In Polar Security Cutter; Talks Interim Purchase,” Defense Daily, October 19, 2021)

Comparison to Successful Programs

Admiral Schultz offered COVID-19 and inexperience in building ‘heavy icebreakers’ as excuses for the continued delays. For comparison, I’d like to highlight some other icebreaking programs that have built large or complex vessels that ran during the same time as the U.S. Coast Guard’s efforts.

I believe that it is fair to consider commercial efforts, given that the PSCs are being built using at least some commercial standards, as cited by the Congressional Research Service1:

The Coast Guard and Navy have carefully reviewed the specific operational requirements for new heavy polar icebreakers, and have adjusted some of those requirements to help reduce their acquisition cost.

The design for the heavy polar icebreakers will rely less on military specifications (MilSpecs) and more on civilian commercial shipbuilding specifications than it might have under a more traditional military ship acquisition approach.

For more on the comparison between MIL-SPEC and commercial standards:

The modern commercial and international standards for survivability and redundancy in icebreakers are quite high. I will consider both large ships and ships that contain significant new technology, where the technical risk is high.

Yamalmax Arc7 LNG Carriers

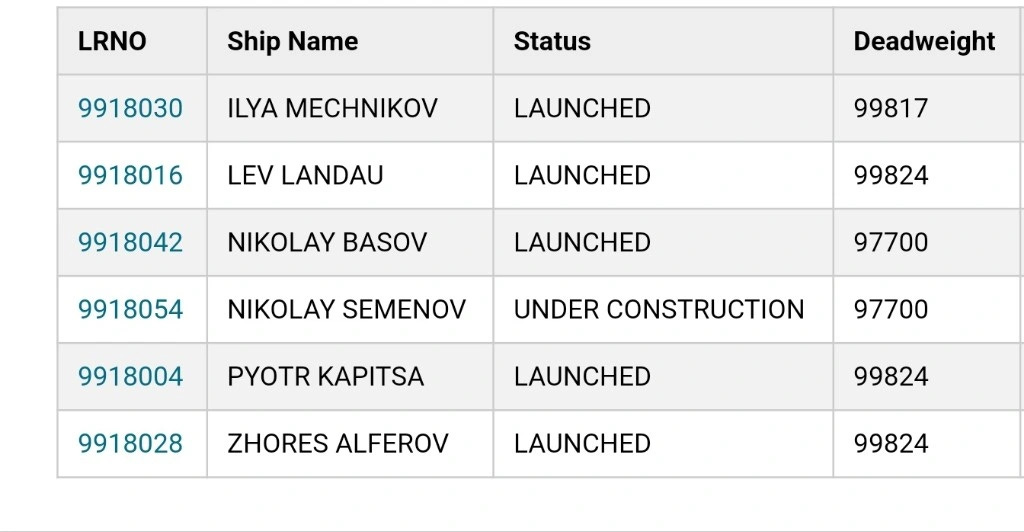

In the past eight years, Hanwha, then known as Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering (DSME) has designed and built 21 large ice-capable LNG carriers for use along Russia’s Northern Sea Route (NSR). These designs are based on concepts developed by Aker Arctic of Finland.

Arc7 LNG Carriers

In July of 2013, DSME won a tender to build up to 16 Arc7 (Polar Class 3) ice-class tankers at a cost of $320 million each.

Here is the timeline for the design and construction of Christophe de Margerie, the first vessel of this new class:

DSME built more than just one. Here is a complete list of these Arc7 LNG Carriers built, with the year delivered:

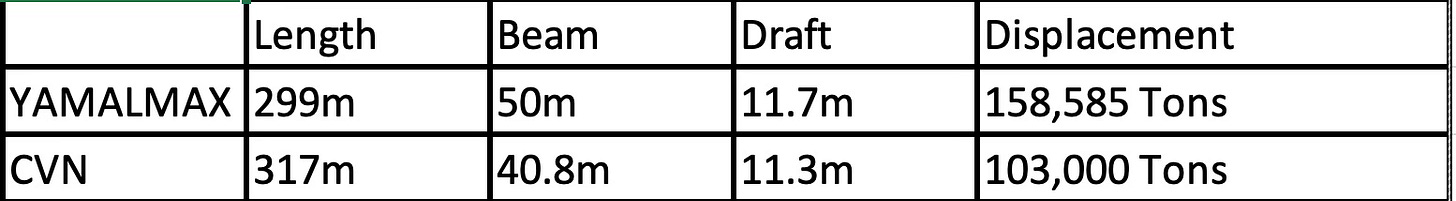

These vessels- known as Yamalmax- are larger than Nimitz-class aircraft carriers.

Icebreaking capability: Comparable to the U.S. Coast Guard’s Heavy Icebreaker Polar Star, which can break 6 ft of ice at 3 knots and is capable of penetrating 21 ft ice ridges3. In ice trials, the Christophe de Margerie made 7.2 knots (astern) and 2.5 knots (ahead) in 1.7m (5 ft) thick ice and penetrated a 15m (49ft) ice ridge. A double acting ship, the Christophe de Margerie is designed to sail forward in open ocean and lighter ice conditions but breaks the toughest ice in the astern direction. In a post on X/Twitter, Aker Arctic observed that the Christophe de Margerie outperformed an Arktika-class nuclear powered icebreaker in ice ridge penetration during ice trials. Christophe de Margerie was going astern, using her modern azimuth propulsion to grind through the ridge, while the Arktika was ramming and backing.

Today, DSME is known has Hanwha Ocean, and they are now owners of Philly Shipyard:

Improved LNG Carriers

Aker Arctic and DSME, along with Novatek, developed a follow-on vessel to meet the needs of Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 project. In 2020, DSME signed an agreement to build six vessels that would be capable of year-round operation along the NSR. They have a new hull design featuring a bow more optimized for icebreaking, are narrower (to more easily use channels opened by icebreakers, if needed) and are slightly more powerful (51 MW instead of 45 MW) than the original Yamalmax design.

Sanctions on Russia and those specifically on the Arctic LNG 2 project mean that although five of the six vessels are complete, none have entered service. DSME cancelled its contract with Sovcomflot for three vessels when sanctions on Russia resulted in non-payment. (Note: Total contract cost of $872 million). However, DSME continued to build these three vessels alongside the three ordered by Mitsui OSK Lines (MOL) of Japan.

Le Commandant Charcot

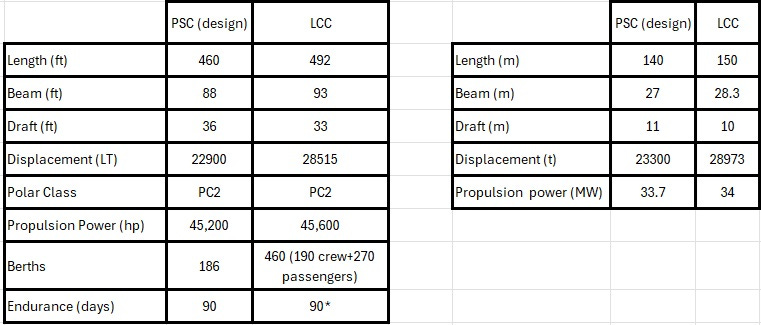

I’ve written extensively about this amazing polar icebreaker that disguises itself as a luxury cruise ship. This is an apt comparison with the Polar Security Cutter for several reasons:

This is a new design. There had never before been an icebreaker built to Polar Class 2 specifications. Additionally, Charcot is dual fuel, another first for polar icebreakers.

Charcot is built to high survivability specifications. The SOLAS safe return to port notation means that the ship must be able not only to survive, but to return to port after the complete destruction of a watertight space via fire or flooding. It is the resulting compartmentalization and staggering of key pieces of equipment that make this vessel’s survivability comparable to a MIL-SPEC vessel.

Since being delivered, Charcot has operated in all areas in which the Polar Star (the U.S. Coast Guard’s sole ‘heavy icebreaker’) operates, including Antarctic waters near McMurdo Station.

Charcot’s planning began differently, with Ponant (the customer) working closely with Aker Arctic of Finland to identify the ice conditions in which the ship would operate. With the necessary ice class and endurance determined, design and construction proceeded. At 68 months from design start to the North Pole, this is longer than some other vessels (like Polaris2), due to the first-of-type nature of Le Commandant Charcot.

Construction Timeline

Size and Icebreaking Comparison with the Polar Security Cutter:

For more on Charcot:

Current Status of the Polar Security Cutter:

I understand that now that ‘construction’ has begun on the first Polar Security Cutter, many are inclined to breathe a sigh of relief and think that the problems associated with the PSC have been overcome. A look back on some projections- including the most recent ones- suggest that this is not a wise course of action. As gCaptain reported in March of 2024:

Bollinger Shipyards began work on up to eight prototype modules in July 2023. According to a Coast Guard spokesperson, work on the first three modules remains ongoing.

According to Bollinger Shipyards the completion of each test module was expected to take around four months.

That original timeline appears to be slipping as nine months later not a single module has been completed.

“As of this month, unit 1 is approximately 42% complete; unit 2 is approximately 27% complete, and unit 3 is approximately 5% complete,” the Coast Guard elaborated.

I am unable to find current statistics for how many modules are complete. The U.S. Coast Guard’s December 23, 2024 press release celebrating the beginning of construction offers no assistance:

The approval incorporates eight prototype fabrication assessment units (PFAUs) currently being built or planned.

This makes it impossible to tell whether the pace of work on the PFAUs has met its target. And if it has not, this means further delays for the program.

GAO Documented Risks:

A GAO Report on the PSC from December of 2024 notes the following:

A November 2023 draft schedule indicated that it will take 1 year longer to build the lead cutter compared to the previous schedule, or over 5 years in total.

If this draft schedule comes to pass, the soonest the lead cutter may be operational is 2030. Program officials said there is some risk of additional delays to start construction due to ongoing contract negotiations between the program and the shipbuilder to revise the schedule and agree on the revised cost of each of the first three Polar Security Cutters. Coast Guard officials said that an updated acquisition program baseline schedule will be released after negotiations are completed with the shipbuilder.

In August 2024, a DHS briefing indicated that starting construction by the end of 2024 was high risk given the state of the program and rate of design completion, meaning there are likely more delays forthcoming to the program.

This last point is particularly noteworthy- starting construction in 2024 was high risk, and there are likely more delays forthcoming.

Comparisons

Here is a simple chart showing program length, vessel type, and cost of the programs I mentioned above:

PSC Start Date: February 28, 2013, when, according to a U.S. Coast Guard press release, an Integrated Project Team had completed the mission needs statement for the new heavy icebreaker and had begun working on a Concept of Operations (CONOPS).

PSC Cost: Estimate from the Congressional Budget Office, May 2024.

As mentioned earlier, I used the PC3 LNG tanker program and Le Commandant Charcot as comparison programs because they ran at the same time as the Polar Security Cutter program. Specifically, this would allow the outside observer to see how COVID-19 affected the programs in question. I added in Polaris to show what building to a more straightforward requirement looks like, even though the Polaris program introduced several innovations.

Charcot was designed by a Finnish company, her hull was built at Vard’s shipyard in Romania, its Azipods were installed in France, and it was outfitted in Norway. All of this happened during the height of COVID-19. International travel and in-person work was required; yet somehow it got done. Of course, Vard had to pay a daily penalty for late delivery of 150,000 Euros.3

Conclusion:

Reading back through the documentation since 2013 has only added to my caution concerning the PSC. Early delays were explained away as allowing for more opportunities to refine the plan which would reduce later risk. Yet although construction official began in December of 2024, the PSC’s detailed design remains incomplete, the program’s current cost and schedule are unknown, yet there is an optimism that “everything will be fine.”

The comparison with commercial programs- particularly the complex nature of Le Commandant Charcot and the volume work done by Hanwha- show that the best course of action, if the U.S. Coast Guard is serious about acquiring icebreakers in a timeline that matters, is to look to allies with a proven record in building icebreakers. For this to happen, President Trump will have to issue a Title 14 waiver and Congress must support it. Yes, this waiver will streamline and simply the process. I expect U.S. shipyards will resist this, but in doing so they put the U.S. Arctic Strategy at risk. Yes, the U.S. Government must fix its acquisition processes. But in parallel with that, it needs to build ships. It simply cannot wait any longer.

What we cannot afford to do is to assume that all will now go well with the Polar Security Cutter Program.

For more information on Finland’s capabilities:

All the Best,

PGR

Coast Guard Polar Icebreaker Program: Background and Issues for Congress. April 18, 2018 edition.

Polaris, a more straightforward design, took about three and half years from the initial design tender (February 11, 2013) to the delivery of the vessel (September 28, 2016).

According to the documentary Megastructures: Icebreaker produced by National Geographic, UK.

Again, Peter, suggesting foreign shipyards build USCG icebreakers...be VERY careful what you wish for! If it was simply building a good icebreaker that could get to McMurdo station, that would be one thing. The Polar Security Cutter is something quite different.